One of Britain’s most prestigious art events is the Summer Exhibition, and in 1987, a watercolour painting by a 39-year-old artist named Arthur George Carrick was submitted for consideration.

This yearly event at London’s Royal Academy allows budding painters an opportunity to show their work alongside that of established masters. Each year, thousands of British people contribute their writings. The vast majority of them are turned down.

Although Carrick’s watercolour depicting a few trees and a farmhouse against a pale blue sky was relatively unremarkable, the show’s organisers obviously saw potential in it. They picked it to be in the programme out of 12,250 others.

King Charles III of England has been actively engaged in British cultural life as both a creator and a patron of the arts throughout the whole of his reign.

The King is generally characterised as a cultural conservative in Britain because to his well-known appreciation of classical architecture. This is supported by the fact that he is an avid operagoer, patron of the arts, and co-founder of both a drawing school and an institution for traditional arts.

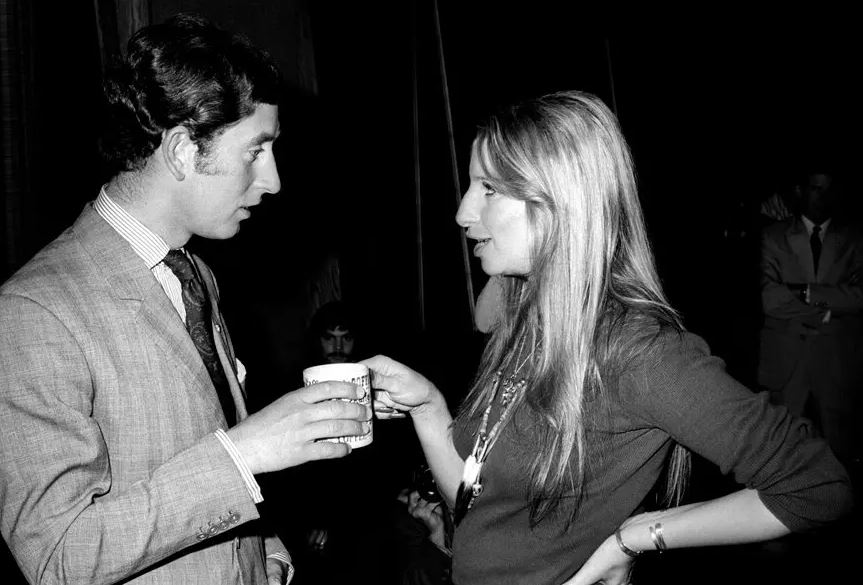

However, he is the first British monarch to come of age during the golden age of mass media, so many of his preferences reflect this. In interviews, Charles has shown his appreciation for the work of Barbra Streisand and surreal comedies such as “Monty Python’s Flying Circus” and “The Goon Show.” The Philadelphia soul group The Three Degrees and Leonard Cohen are two artists whose work he admits to enjoying.

Charles has more diversified hobbies than any other king in almost a century. Charles’s interest in the arts and entertainment is reminiscent of the preoccupations of numerous former monarchs, including some who ruled centuries before Queen Elizabeth II, who died last year.

Charles I, a patron of artists like Rubens and Van Dyck in the 17th century, amassed one of Europe’s greatest art collections. After a long shutdown caused by puritan rebels, his son Charles II restored British theatres and established the foundation for the modern West End. George III amassed an outstanding collection of 65,000 volumes in the 18th century, which became the backbone of the British Library.

Charles, unlike his predecessors, is typically characterised by what he dislikes rather than what he likes. Back in the 1980s, when he was still Prince of Wales, Charles began using his platform to rail against contemporary architecture and advocate for a return to classical styles. He tried to put a stop to various glass-and-steel construction projects by personally intervening on multiple occasions. This has earned him the wrath of several British architects, who have called his intervention unlawful.

The future king’s interest in classical music was nurtured by the Queen Mother, and he picked up the trumpet in his boarding school ensemble. Charles said that during a practise an instructor yelled, “Those trumpets!” and Charles felt he was doing well until then. Put an end to the fanfare. He shifted to the cello.

The documentary claims that he had no professional painting instruction but had taught himself watercolours. Charles had been producing images of rural scenery and royal estates for decades before he discreetly put his art into the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1987.

During his travels abroad, Charles has also commissioned artists to document the experience for the royal art collection. In 2014, Charles took a trip to Mexico and Colombia with the help of figurative painter Diarmuid Kelley, who said that the king gave him free reign to paint anything he wanted, despite the fact that courtiers had asked him to include Charles in the works. When asked what he drew, Kelley answered, “nothing outlandish or avant-garde,” referring to his sketches of a temple and a street scene.

No matter what you think of Charles’s taste, composer O’Regan says it’s a fantastic time to have an arts aficionado on Britain’s throne. In light of the recent cuts to government funding for the arts, O’Regan praised the new coronation music commissioned by King George VI as “a clear statement about the importance of the arts.”

O’Regan chimed in that kings shouldn’t tell countries how to run, but Charles was demonstrating the value of culture.