Federal regulators have taken a significant step in safeguarding the health of miners by implementing new protections against silica dust exposure, a hazard known to cause deadly lung ailments. These changes, long recommended by government researchers, aim to limit concentrations of airborne silica—a mineral commonly found in rock that becomes lethal when ground up and inhaled. The new requirements, announced by the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), will impact over 250,000 miners involved in extracting coal, metals, and minerals used in various industries, including cement and electronics.

This development comes after a lengthy regulatory process spanning four presidential administrations. Despite the prolonged delay, the need for enhanced protections became increasingly urgent as studies documented a resurgence of severe black lung disease among younger coal miners. Poorly controlled silica was identified as a likely cause, prompting the MSHA to take action.

Chris Williamson, head of the MSHA, emphasized the inadequacy of existing standards, stating, “It should shock the conscience to know that there are people in this country who do incredibly hard work that we all benefit from, yet are already disabled before they reach the age of 40.”

Acting Secretary of Labor Julie Su announced the new requirements in Pennsylvania, marking a significant milestone in efforts to safeguard miners’ health. These regulations follow similar protections established by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) for workers in industries such as construction and fracking.

While both mine safety advocates and industry groups generally support the rule’s central change—halving the allowed concentration of silica dust—there are divergent views on enforcement. Mining trade groups argue that the requirements are overly broad and costly, while miners’ advocates express concerns about companies’ ability to police themselves effectively.

The dangers of silica dust exposure have been known for nearly a century, dating back to a tragic industrial disaster in West Virginia. Despite early recognition, recommendations to reduce silica exposure have languished for decades. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) first recommended lowering silica limits in 1974, followed by similar recommendations from a Labor Department advisory committee in 1995.

Efforts to enact a silica rule faced numerous obstacles during subsequent administrations, including political considerations, industry opposition, and competing priorities. While progress was made on a separate rule to regulate overall dust levels in coal mines, addressing silica exposure remained a challenge.

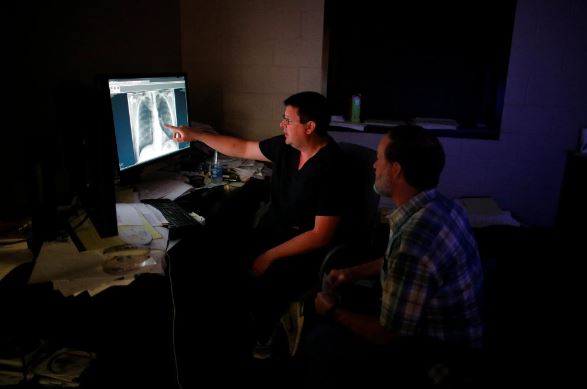

The resurgence of black lung disease in recent years underscored the urgency of implementing silica protections. Changes in mining practices, resulting in increased silica dust production, contributed to rising rates of the disease among miners. Clinics in Appalachian regions began seeing younger miners with advanced stages of lung disease—a troubling trend that prompted renewed calls for action.

Despite the new rule adopting the silica limit recommended in 1974, concerns remain about enforcement. Regulations largely rely on mining companies to collect samples and demonstrate compliance, raising questions about the accuracy of reported data. Miners have reported pressure to manipulate sampling results, leading to artificially low readings.

While the rule’s effectiveness may not be immediately apparent, it represents a significant step toward addressing a longstanding health hazard in the mining industry. By implementing stricter silica protections, regulators aim to prevent future cases of debilitating lung disease among miners—a goal that remains paramount in ensuring their health and safety.