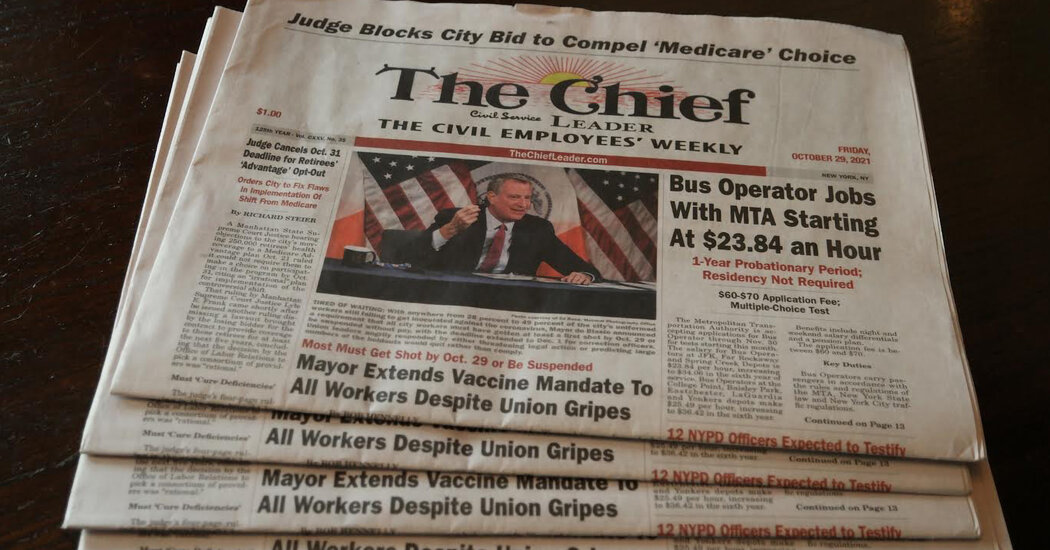

The top item in The Chief-weekly Leader’s print edition, a journal that has long covered New York City’s civil employees, is often about the most sought-after job opening in the city. “Bus Operator Jobs with the MTA Starting at $23.84 an Hour,” the headline said last week.

Years have passed since the publication of the paper, a broadsheet launched in 1897 for firemen, has followed the parallel downward trajectories of both the newspaper business and the labour movement. Richard Steier, the magazine’s senior editor for the last 23 years, was forced to take wage cutbacks in 2019 and 2020.

Unexpectedly, something occurred in August. A businessman acquired The Chief from the family that had owned it for more than a century, with the goal of transforming it into an influential national voice for public and private-sector workers.

Ben August, the journal’s new owner, is an unexpected custodian for a publication with roughly 30,000 subscribers, the vast majority of whom are New York City municipal employees. The sale of a human resource services firm that he founded some years ago helped him to make a fortune. Since then, he has devoted his time to his vineyard in Napa Valley and to a non-profit organisation dedicated to determining who penned the plays credited to Shakespeare in the first place. Mr. August thinks it was most likely Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, who was responsible, and he has named a wine after him, Earl 17.

Aside from that, Mr. August is quite enthusiastic about the topics addressed by The Chief. In response to my inquiry as to why he had purchased the newspaper, he said, “Labor is underrepresented, organised labour may be making a return, and I would want to light those fires if at all possible.”

His timing is impeccable. Since 1965, according to a Gallup poll conducted this October, more Americans support labour unions than at any other time in history. President Biden’s National Labor Relations Board is significantly more sympathetic to their plight than President Donald Trump’s National Labor Relations Board. A tight labour market has also changed the balance of power in favour of employees. “Empowered by labour and supply shortages that make companies more vulnerable, and irritated by what they perceive to be unfair treatment during the epidemic, employees are rising up for a better deal.

And the anticipated return of The Chief is just one of a few signs that, at a time of political upheaval, economic change, and a pandemic-driven emphasis on how we work, labour has emerged as a popular news topic.

Steven Greenhouse, a former labour correspondent for The New York Times, told me that he was “the sole full-time daily labour reporter” for a period of time in the 2000s. There are now at least a dozen of them working for traditional media sources as well as internet publications such as Vice and HuffPost.

The shift may also be seen in the manner in which some of the most important economic stories are reported. In today’s world, reports on corporations ranging from Amazon to Uber are less likely to fall into the boosterish category of “gee-whiz” technology tales. And the stories of heroic entrepreneurs have given way to stories about their employees – stories about the complicated and often harmful impacts of the digital revolution on warehouse workers, taxi drivers, delivery drivers, and white-collar workers, among other groups.

It is possible to find everything from traditional newspaper reporting to outright advocacy in the new brand of labour journalism, and the most ambitious new entrant on the scene hails unapologetically from the Bernie Sanders stream of class-based American politics: More Perfect Union, a nonprofit news outlet that quietly launched in February. Part of the leadership of the group comes from Faiz Shakir, a former campaign manager for Bernie Sanders’ 2020 presidential campaign, as well as Nico Pitney, a former senior editor at The Huffington Post and NowThisNews.com.

Labor unions are not allowed to contribute to More Perfect Union, a video-centric platform with a staff of 24 and funding from George Soros’ Open Society Foundation, among other sources. Mr. Shakir said that the organisation does not accept money from labour unions. However, it has proven to be a powerful ally on picket lines, bringing emotionally charged statements from striking employees to the media. In addition to receiving over two million views on Twitter, videos highlighting Amazon’s anti-union efforts and working conditions at Frito-Lay and Kellogg’s have garnered a regular stream of interaction on TikTok, which the site’s administrators see as a method to reach those beyond the chattering elite.