It was three years ago this week that a catastrophic wildfire rushed through Paradise, Calif., and claimed the lives of 85 people while destroying more than 13,000 houses. One of such residences was the wood chalet-style cottage in which Mike and Jennifer Petersen resided, which was constructed by Ms. Petersen’s grandparents in the 1960s and is still standing today.

“I don’t even have a good enough language to express what that day was like,” said Mr. Petersen, who recalls driving through the flames to escape with his wife and his two kids, who were 18 and 21 at the time. “It was a horrible day,” he said. “It was completely insane.”

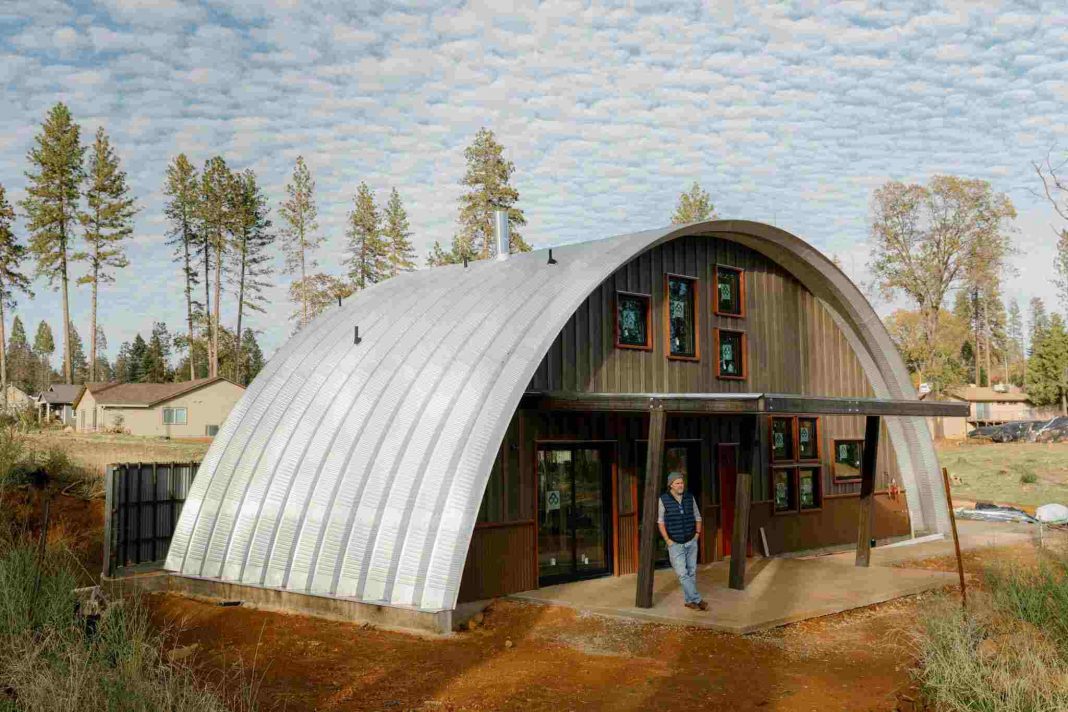

They are now rebuilding on the same location, but not in the manner in which Ms. Petersen’s ancestors constructed their home. Q Cabin will be built, which will be 1,400 square feet in size and constructed of noncombustible steel in the shape of a half-circle. From the exterior, the home, which cost a little less than $350,000, resembles a modest, well-designed aircraft hangar, which is appropriate given its size. The inside is an open-plan modern residence.

Mr. Petersen, who owns and operates a hardware shop, one of the few remaining companies in the town, said he wanted to construct a home that was both elegant and sturdy at the same time. In his words, “If there is going to be anything that can withstand an earthquake, this would be it.”

A disaster-proof house is something that many people want. The Petersens are not alone in their goal. The construction of homes in natural-disaster-prone locations around the United States is becoming more popular as people seek to protect their families from a wide range of disasters. As a result, although some of these technologies are in their early stages, they provide a look into the future of building in broad swathes of the nation as climate change ushers in an era marked by more regular wildfire, storms, and flash floods.

According to CoreLogic, a real estate data analytics business, as much as a third of the housing stock in the United States — or around 35 million homes — is at high risk from natural catastrophes linked to climate change. “These dangers have always existed,” said Tom Larsen, a partner at CoreLogic who specialises in risk modelling. “However, every time a calamity draws near, people have the sensation of thinking, ‘Wow, that might be me.'”

Furthermore, climate-related calamities are expected to worsen. As predicted by CoreLogic, a typical severe coastal storm in Florida might cause flooding in 300,000 residences 30 years from now, more than tripling the number of properties already impacted.

Originally inspired by the Quonset huts built during World War II to store military supplies, Vern Sneed, a general contractor and the founder of Design Horizons, the company that manufactures Q Cabins, explained that he became interested in this type of building because it could be constructed quickly and inexpensively. (However, labour shortages and increased material prices have caused this to shift lately.) His second favourite feature of Q Cabins was its distinctive design, which helped them stand out among other prefabricated houses when he first began promoting them back in 2010.

Later, he discovered that the homes he was selling were fire resistant due to the fact that they were virtually completely made of steel. As a result, he added noncombustible sheathing, which, according to him, renders the major structural components noncombustible up to 2,600 degrees Fahrenheit in principle. It’s possible that they will still burn in some conditions, according to him, and none of the Q Cabins have been tested in genuine wildfires. Following the 2018 fire, Mr. Sneed relocated his firm to Chico, which is about 20 minutes away from Paradise, in order to offer the factory-built Q Cabin kits to customers who were rebuilding their homes.

The region has seen him sell a number of structures ranging from modest storage sheds to 6,000-square-foot houses. He estimates that another dozen are in the works, including one that Missy Barnard and husband David Barnard are now constructing in the neighbourhood. The Q Cabin, which was built by a former emergency department director, convinced Ms. Barnard and her husband to abandon their plans to rebuild their 1970s ranch-style home with a more conventional one.

The Barnards are doing the majority of the work themselves, working six or seven days a week, which has proven to be a difficult undertaking. “I’m not leaving this place ever again,” Ms. Barnard said after the work was completed.

In the University of California at Davis, Professor Michele Barbato is researching compressed earth block construction, a 10,000-year-old process for making bricks from tightly compacted soil and mud that has been blended with cement, limestone, or a chemical stabiliser to make it water-resistant.

Fire, hurricane, and wind resistance tests conducted at Dr. Barbato’s laboratory have shown that earth-block dwellings are very resilient to these elements, he claimed. However, he said, the strongest proof may be found in constructions that have stood the test of time for thousands of years, such as the Great Wall of China: “We can create the same sort of structures now.”

Chief executive of Redfin, a Seattle-based real estate firm, Glenn Kelman has invested in the technology because he believes it is a potential answer in an era of climate change, according to the company. According to him, “people don’t change until they’re forced to.” “We’ve reached a situation where people are forced to.”

Although the vast majority of new homes are built to standards requiring them to be resistant to earthquakes, floods, blizzards, hurricanes, and wildfires, the National Association of Home Builders reports that the vast majority of existing homes in the United States were built before the 2000 International Residential Code and may require upgrades to make them safer. However, rather than the possibility of future calamities, aesthetics and cost continue to be the primary considerations influencing the design selections of many homeowners.