Doug Olson was feeling a little drained back in 1996. When a doctor checked him, she gave him a disapproving look. While prodding him in the neck, she stated, “I don’t like the feel of those lymph nodes.” She made the decision to get a biopsy. The end outcome was a scary experience. He was suffering with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, a kind of blood disease that mostly affects older individuals and accounts for almost a quarter of all new occurrences of leukaemia in the United States.

Six years passed without any sign of the malignancy developing. After then, it began to expand. However, the malignancy returned after four rounds of chemo were administered. He had almost reached the end of his treatment options when his oncologist, Dr. David Porter of the University of Pennsylvania, gave him the opportunity to be one of the very first patients to try something completely new, known as CAR T cell therapy. He accepted the offer.

According to Dr. Carl June, the primary investigator for the experiment at the University of Pennsylvania, the notion for this kind of treatment was “far out there” at the time, and Dr. June had lowered his own hopes that the cells he was sending to Mr. Olson as therapy would survive.

Ten years later, however, he reveals that his expectations were utterly misplaced. Dr. June and his colleagues, Dr. J. Joseph Melenhorst and Dr. Porter, released a study in Nature on Wednesday in which they claim that the CAR T therapy caused the cancer to disappear in two out of the three patients who participated in that early trial. All of them were suffering from chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. What was most surprising was that even after the cancer had been eradicated, the CAR T cells lingered in the patients’ bloodstreams, acting as sentinels throughout the body.

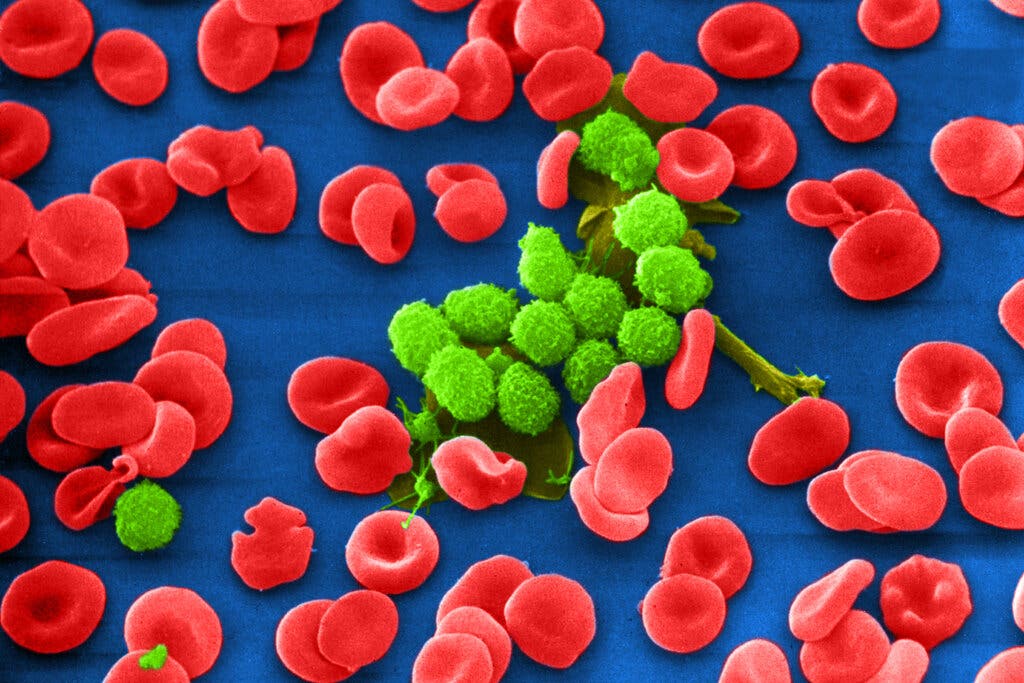

Remove T cells from a patient’s blood (white blood cells that fight infections) and genetically alter them to combat cancer is the method used in the therapy. After that, the changed cells are reintroduced into the patient’s circulatory system.

In the instance of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, the kind of cancer that Mr. Olson was diagnosed with, the malignancy affected B cells, which are immune system cells that produce antibodies. T cells in a patient’s body are trained to detect and kill B cells in the body. If the therapy is successful, it will result in the annihilation of every B cell in the human body. Patients would be left with no B cells if this happened. However, there will be no cancer. Antibodies in the form of immunoglobulin infusions would be required on a regular basis by these patients.

Many patients with blood malignancies have benefited from this treatment, which has been especially helpful in individuals with acute leukemias and other blood cancers. Mr. Olson, on the other hand, has chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, often known as CLL, and has had less success than others with the disease. CAR T treatment induces remission in around one-third to one-fifth of patients with that malignancy, although many of those who have remission eventually experience recurrence.

It is not only important to understand why some patients relapse or become resistant to medication, but it is also important to understand why other people are cured.” The study’s lead author, Dr. John F. DiPersio, chairman of the division of oncology at Washington University in St. Louis, who was not engaged in the research, expressed his disappointment.

CAR T therapy has also been associated with catastrophic adverse effects in some patients, including high fevers, comas, dangerously low blood pressure, and even death – although the scary symptoms in the majority of patients disappear within a short period of time. It has not been shown to be effective in persons with solid tumours, such as those present in illnesses such as breast and prostate cancer.

At first glance, the CD8 cells seemed to be performing just as predicted by Dr. June’s research. Mr. Olson and the first patient in the trial, William Ludwig, who was likewise healed of his cancer but died last year from Covid-19, were both cured virtually immediately after receiving the modified CD8 T cells.

After the CD8 cells completed their task, they stayed in the bloodstream but, in an unexpected turn, they transformed into CD4. As a result, when the Penn research withdrew CD4 cells from the blood samples of Messrs Ludwig and Olson, they discovered that those cells were capable of killing B cells in a laboratory setting. Dr. DiPersio saw that the CD4 cells had transformed into assassins or, as he put it, “at the very least guardians” who might “keep the tumour cells at bay and invisible in the patient for years.”

Is it possible for CD4 cells to persist in the bloodstream if there are no cancer cells to kill? Or were they there because the leukaemia had not really disappeared but was instead attempting to resurface, only to be destroyed by CD4 cells in the process?

If these tumours do not reappear within two to five years, the risk of a recurrence is minimal, according to Dr. Hagop M. Kantarjian, chief of the department of leukaemia at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, who spoke at the conference.

Mr. Olson, who is now 75 years old and resides in Pleasanton, California, is content with his life. That his doctor happened to be an investigator in that research study a decade ago still makes him shake his head.