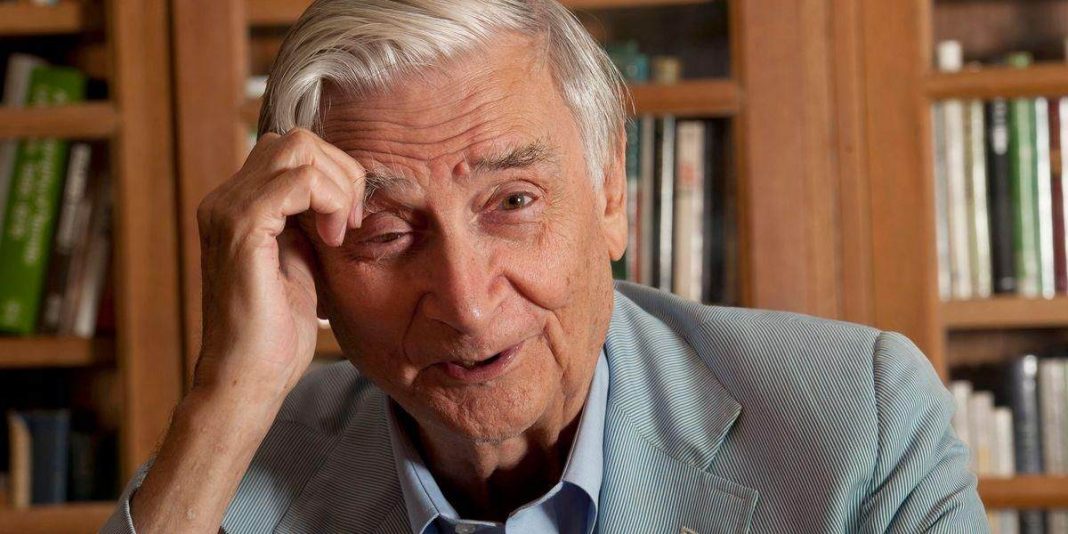

On Sunday in Burlington, Massachusetts, Edward O. Wilson, a scientist and novelist who carried out groundbreaking research on biodiversity, insects, and human nature — and was awarded two Pulitzer Prizes in the process – passed away. He was 92 years old.

During the 1950s, when Dr. Wilson started his career in evolutionary biology, the study of animals and plants was considered by many scientists to be an antiquated and outmoded pursuit. A new generation of molecular scientists was gaining their first glances of DNA, proteins, and other intangible building blocks of life. Dr. Wilson has dedicated his life’s effort to putting evolution on an equal footing with other theories.

If molecular biology can acquire new intellectual rigour and creativity, how may our “appearingly old-fashioned fields” gain new intellectual rigour and originality, he wondered in 2009. He provided an answer to his own query by establishing new areas of investigation.

Doctor Wilson was a specialist in insects, and he researched the evolution of behaviour, attempting to understand how natural selection and other factors could develop something as extraordinary sophisticated as an ant colony as a result of natural selection. Following that, he advocated for this kind of study as a method for making sense of all behaviour, including our own.

As part of his effort, Dr. Wilson authored a series of publications that not only inspired his fellow scientists, but also reached a wide readership in the general public. Dr. Wilson’s book “On Human Nature” was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction in 1979, and his book “The Ants,” which he co-wrote with his lifelong collaborator Bert Hölldobler, was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1991.

His goals also drew the ire of a large number of people. Some people were critical of what they regarded to be oversimplified depictions of human nature. Several evolutionary scientists chastised him for changing his mind on natural selection so late in his professional life.

Dr. Wilson attended Harvard University and received his Ph.D. in 1950. In order to further his graduate studies, he started on a lengthy voyage in 1953 to examine the worldwide variety of ants, beginning in Cuba and continuing on to Mexico, New Guinea, and isolated islands in the South Pacific.

Dr. Wilson joined the Harvard faculty in 1956 and has been there ever since. As a new professor, he jumped right into exploring a variety of scientific problems at the same time. His study included looking for a theory that might make predictions about the variety of life, which he found in one line of inquiry. Robert MacArthur, a biologist at the University of Pennsylvania at the time, proved to be the ideal collaborator for this project when he met him in 1961.

As a result of natural selection, which transforms a species as some individuals have more offspring than others, Dr. Wilson found it difficult to explain ant behaviour in terms of evolution. Ants are very cooperative, to the point that the daughters of a queen ant are often infertile, sacrificing their own reproductive success in order to benefit hers.

He discovered a solution — at least for the time being — in the work of William Hamilton, a PhD student from the United Kingdom. Mr. Hamilton stated that scientists should pay less attention to individual animals and instead concentrate on their DNA.

These restrictions were overlooked by Dr. Wilson’s detractors. Many readers of The New York Review of Books expressed their displeasure with the field of sociobiology, accusing it of attempting to revive tired old theories of biological determinism — theories they claimed were responsible for the enactment of sterilisation laws and restrictive immigration policies in the United States between 1910 and 1930, as well as the establishment of gas chambers in Nazi Germany.

It, like so many of Dr. Wilson’s ideas, prompted other scientists to do more study of their own as a result of his work. According to a research released in 2018, Dr. Pimm and his colleagues might bring Dr. Wilson’s idea to fruition if they devise a methodical approach to selecting which sites should be preserved.