Skin contains thousands of different microorganisms, and the mechanisms in which they contribute to healthy skin remain mainly a mystery to scientists today. According to some reports, the puzzle is becoming increasingly more complicated: In an article published Thursday in the journal Cell Host & Microbe, researchers who studied the different kinds of Cutibacterium acnes bacteria on 16 human volunteers discovered that each pore was a microcosm of the larger microcosm of the larger microcosm. Every pore contained a single strain of the acnes bacteria C. acnes.

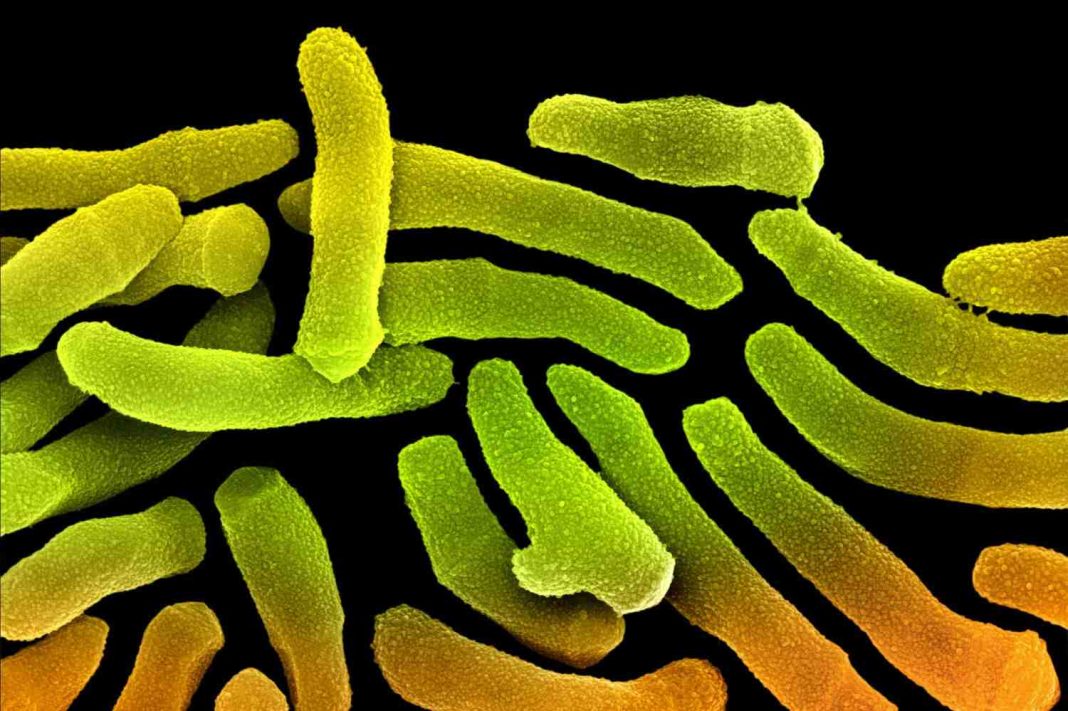

C. acnes is a naturally occurring bacterium that is the most prevalent on the human skin. According to Tami Lieberman, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and one of the authors of the current article, the relationship between the virus and acne remains unclear. If biologists want to understand the relationship between the inhabitants of your face and the health of your skin, it will be critical to first determine whether different strains of C. acnes have distinct talents or niches, and then to determine how the strains are distributed across your skin’s surface.

Dr. Lieberman and her colleagues collected their samples using a combination of commercially available nasal strips and old-fashioned squeezing using a comedone extractor, a tool designed specifically for this purpose. They next spread samples from inside pores on Petri plates, each of which looked a little like a miniature glacier core. This was done using samples taken from toothpicks that had been rubbed over the surface of the participants’ foreheads, cheeks, and backs, which had picked up bacteria that lived on the skin’s surface rather than inside its pores. They allowed the bacteria to grow before sequencing their DNA to determine which ones they were.

Each individual’s skin had a unique mix of strains, but what startled the researchers the most was the discovery that each pore contained a distinct strain of C. acnes, which was previously unknown. The pores were also distinct from their neighbours — for example, there was no discernible pattern connecting the pores on the left face or forehead over the volunteers’ whole body, for example.

In the study’s main author, Arolyn Conwill, a postdoctoral researcher who is also the study’s lead author, stated, “There’s a tremendous amount of variety across one square centimetre of your face.” “However, there is a complete absence of variation inside each and every one of your pores.”

The scientists believe that each pore includes offspring of a single person, which is what they believe is occurring. Dr. Lieberman describes pores as “deep, narrow nooks with oil-secreting glands at the bottom,” which are deep, narrow holes. The cell of Acne vulgaris may be able to sneak inside the pore and begin to multiply, eventually filling the pore with duplicates of itself.

This would also explain why strains that don’t develop very rapidly are able to avoid being outcompeted by faster-growing strains when grown on the same individual. There is no competition between them; instead, they coexist in their own little walled gardens beside one another.

The experts believe that these gardens are not very ancient, which is an intriguing fact. They estimate that the starting cells in the pores they analysed had only been there for around a year before they were discovered.

What happened to all of the germs that used to reside in that area? The researchers are baffled as to what happened to them; they speculate that they were killed by the immune system, succumbed to viruses, or were abruptly jerked out by a nasal strip, paving the way for new founders.

Dr. Lieberman said that the discovery has ramifications for the field of microbiome research in general. For example, taking a simple swab of someone’s skin would never provide any indication of the intricacy found in this research. Moreover, when scientists investigate the prospect of modifying human microbiomes in order to aid in the treatment of illness, the patterns shown by this research suggest that knowledge regarding the location and arrangement of microorganisms, rather than simply their names, will be required. It is possible that physicians may need to clean out a patient’s pores in the future if they wish to replace the existing skin residents with others.

And is it possible that another occupant of our faces plays a part in the way bacteria enters and exits each pore on our faces?

The doctor said that “we have mites on our faces that live in pores and devour germs.” It has not yet been identified what function they play in this ecosystem in terms of the maintenance of C. acnes gardens, although it is likely that they do.