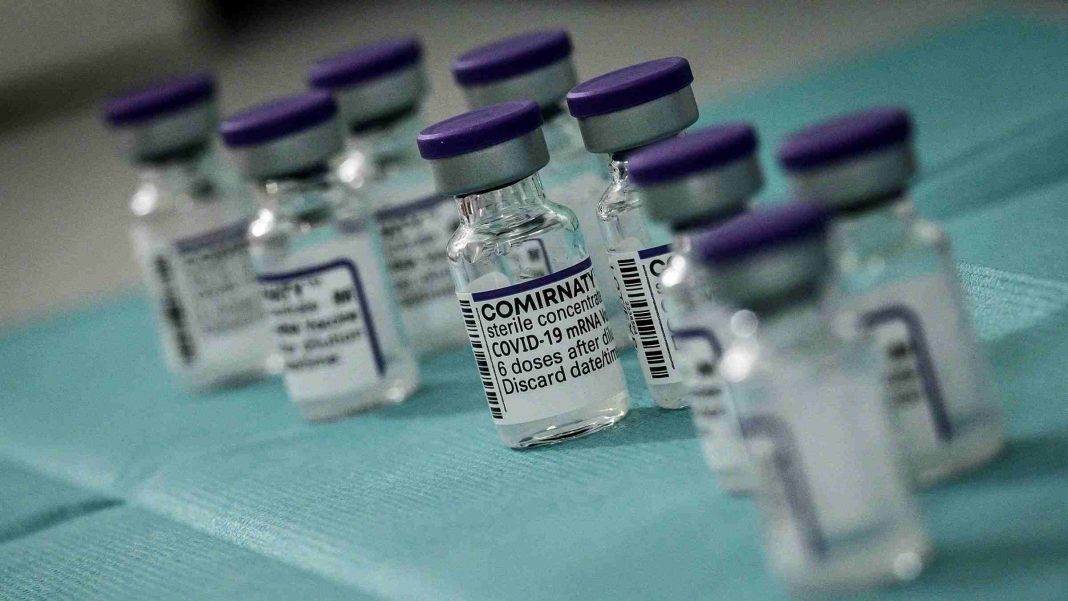

Vaccination manufacturers, Pfizer and BioNTech, said on Wednesday, that laboratory testing have shown that an additional dose of their coronavirus vaccine provides considerable protection against the virus’s fast-spreading Omicron version.

According to the businesses, testing on blood samples taken from persons who had only received two doses of the vaccine revealed much lower levels of antibodies defending against Omicron than against an earlier form of the virus. According to the firms, this shows that two doses of the vaccine “may not be adequate to protect against infection” by the new type.

While the study was restricted in scope (the firms analysed just roughly 39 samples in order to gather answers as quickly as possible), the findings gave a ray of light at a time when uncertainty has returned. In the United States, health agencies are recognising about 100,000 cases each day, hospitalizations are increasing, and fatalities are once again on the increase, virtually all of which are related to the Delta version of the virus.

The corporations issued a press release summarising their results but did not provide any specific data. Their research followed on the heels of a preliminary report on laboratory studies conducted in South Africa, which revealed that Omicron seemed to reduce the effectiveness of two doses of the Pfizer vaccine.

According to the Associated Press, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has registered 43 instances of Omicron infection, the most of which were minor, in around 20 states throughout the United States as of Wednesday. Early modelling and analysis show that this newest variation may be twice as rapid as Delta in terms of growth in certain regions of South Africa and Europe; however, more research is needed to confirm this.

While Omicron seems to be the dominant coronavirus in South Africa, two big hospitals are reporting an increase in the number of children who test positive for the coronavirus after being hospitalised for other reasons, indicating an increase in community transmission there. Cities all across the globe are postponing Christmas and New Year’s Eve celebrations because of unanswered issues regarding the new variant’s transmissibility and ferocity, according to the CDC.

President Biden went out of his way on Wednesday to bring attention to the results of Pfizer-BioNTech, calling them “very, very positive” and stating that they demonstrated that vaccinations continue to be a bulwark against the virus.

However, the results of Pfizer-laboratory BioNTech’s examination of blood samples are not indicative of how the vaccinations would operate in the real world. While antibodies serve as the first line of defence against infection, they are just a small portion of the immune system’s more comprehensive and strong reaction to infection. Because antibodies are the most quickly detected and simplest to quantify, the findings are usually the first to be obtained.

Scientists believe it might take a month or more to fully comprehend the danger posed by the new strain. It is expected that by that time Israel, the United Kingdom, or other nations with advanced health monitoring systems would have acquired more information on whether Omicron will overrun Delta and how well the immunizations will fare in the face of the virus.

The findings of the Pfizer-BioNTech study seemed to emphasise the relevance of boosters in the fight against infection. According to Pfizer’s announcement, blood samples taken from persons who had received a booster injection had antibodies that neutralised Omicron at levels equivalent to those that combatted the original form after two doses.

Dr. Peter Hotez, a vaccination specialist at the Baylor College of Medicine, described the findings as “very wonderful news,” although he cautioned that the researchers only evaluated the levels of neutralising antibodies one month after the booster shot.

In response to severe vaccine shortages in poorer countries, the World Health Organization said on Wednesday that it was too soon to determine whether the vaccines were significantly less effective against Omicron or whether the emergence of the variant necessitated a booster shot for the vast majority of people. The World Health Organization has long opposed widespread rollouts of booster shots due to severe vaccine shortages in poorer countries.

The businesses said that Omicron would not substantially reduce the effectiveness of T-cells, which are responsible for killing infected cells. The researchers discovered sections of Omicron that might be recognised by the T-cells created as a result of the immunisation. The majority of them did not include any alterations.

His observations were that South Africa’s population varied from that of the United States, with a high number of infected young people, a low percentage of those who had been vaccinated, and a high prevalence of HIV, which may cause immune system damage if not treated. Others expressed concern about extrapolating conclusions from a smattering of early reports.

Doctor Bourla said in an interview last week that the business began creating a version of its vaccine targeting Omicron immediately after Thanksgiving and that it expects to be able to manufacture it in large numbers within 95 days. Moderna is travelling along a similar route.

As a result of the virus’s alterations, Pfizer had created two more prototypes in response to the threat of new varieties, but neither had proven to be essential since the original vaccine was effective against them.