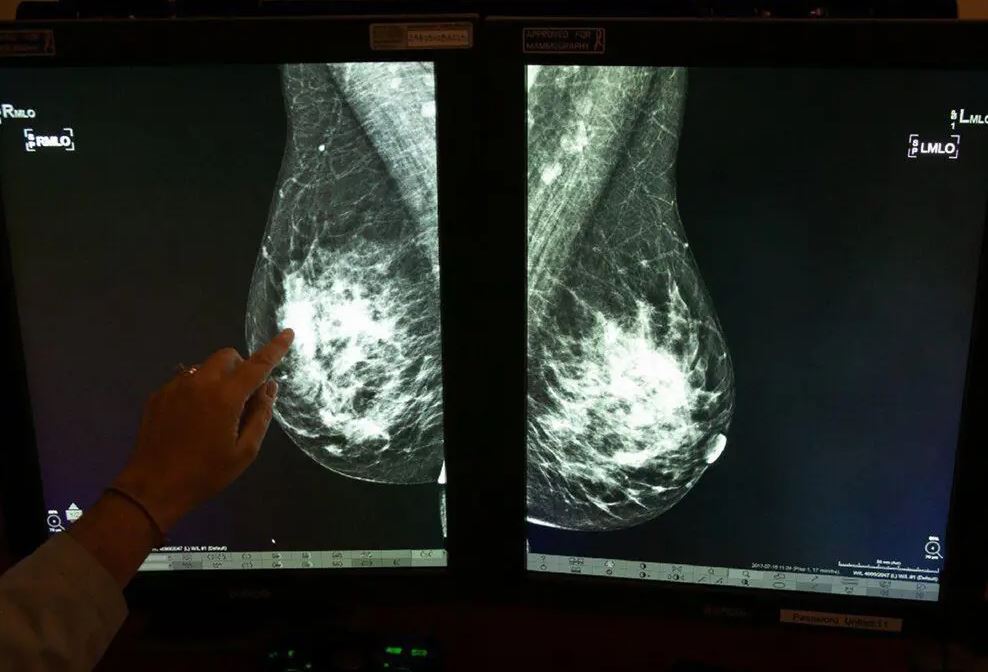

In women, having thick breast tissue has long been recognised by scientists to increase their chance of developing breast cancer. While previous research has shown that breast density does decrease with age, a new study published in JAMA Oncology on Thursday adds a new twist by finding that a slower rate of decline in one breast often precedes a cancer diagnosis in that breast.

Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis looked examined the density of 10,000 women’s breasts over the course of ten years, all of whom were cancer-free at the study’s outset. Over the course of the study’s time period, 289 women were diagnosed with breast cancer; researchers compared the breast tissue changes in these women to those in a control group of 658 women without breast cancer.

those who later were diagnosed with breast cancer had greater baseline breast density than those who did not acquire the disease. When researchers measured the density of each breast independently, they discovered that breasts that developed cancer lost density at a much slower rate than the other breast in the same patient.

Washington University assistant professor of public health sciences and research author Shu Jiang speculated that the results might give an individual and dynamic tool for measuring a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer. She expressed her desire for its rapid implementation into clinical practise, saying, “I hope they can get this into clinical use as soon as possible; it will make a huge difference.”

Dr. Jiang explained, “Right now, everybody only looks at density at one point in time.” However, the density of each breast is measured repeatedly throughout a woman’s life thanks to routine mammography.

She said, “So this information is actually available but not being utilised.” It is now possible for a woman’s risk of acquiring breast cancer to “be updated every time she gets a new mammogram.”

Density of the breasts is increasingly recognised as a risk factor for breast cancer. Imaging scans have a more difficult time picking up tumours in dense tissue.

Dozens of jurisdictions have passed legislation mandating that women be informed by mammography facilities if they have dense breast tissue. The FDA issued a recommendation in March for clinicians to discuss breast density with patients.

This is the first research to reveal a correlation between breast density and its evolution over time.

While more extensive research is needed to confirm the results, American Cancer Society CEO Karen Knudsen described the preliminary findings as “exciting.”

Rather than averaging the two breasts, where it is possible to miss these changes, “this is the first study I’ve seen that looks specifically across time at changes from breast to breast,” Dr. Knudsen stated.

The research concludes that women may make better use of the information they get on breast density and the dangers linked with it. Dr. Knudsen has said that “we need to know how to follow women with dense breasts instead of just alerting them.”

Dr. Knudsen proposed as a potential next study looking at breast density over time in women on breast cancer prevention medication to determine whether the density diminishes.

Those who are experiencing a considerably slower reduction in tissue density may be subject to distinct risk categorization rules, as suggested by Dr. Jiang.