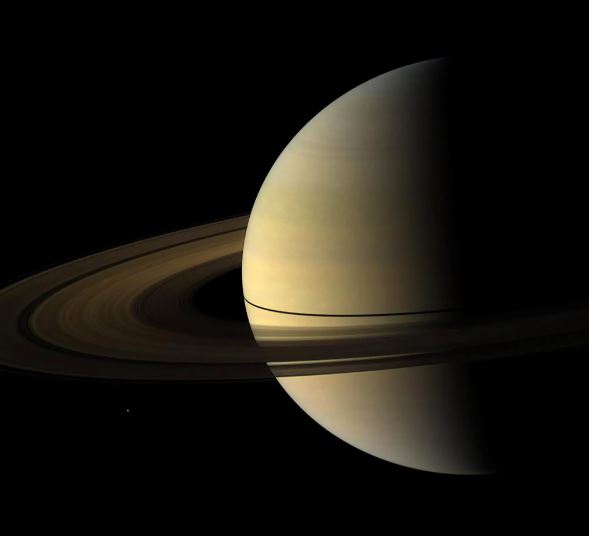

If Saturn didn’t have its rings, it would look quite different. Imagine now that two huge, ice moons are gradually drifting closer together until — kaboom. Chaos. The once-solid has become a liquid. Pieces of diamond explode into the night. Many ice pieces drop near to Saturn, then linger there and dance about the gas giant in harmony, eventually shaping the gorgeous discs of this massive body.

This amazing view is the result of scientists looking into one of the solar system’s biggest mysteries: how and when did Saturn’s rings form?

This week, a research appeared in The Astrophysical Journal that lends credence to the idea that these features are not billions of years old but rather the product of relatively recent astronomical events, such as the collision of two small, frost-flecked moons.

Using Britain’s Distributed Research Using Advanced Computing facility, Dr. Kegerreis and colleagues examined the younger-rings theory. The researchers were able to verify the plausibility of this genesis tale by simulating the catastrophe and its immediate aftermath many times on the supercomputer.

The team’s simulations might help researchers learn more about the birth of planetary systems in general, not just Saturn’s rings. In light of its many moons, Saturn “can be considered a mini-solar system,” according to astronomer Scott Sheppard of Washington’s Carnegie Institution for Science. The formation of planets and moons may be studied in great detail on Saturn.

Saturn is nearly as ancient as the sun, at 4.5 billion years. Before the 13-year Cassini mission to the planet, it was assumed that its rings were also quite old in age. They should have been tarnished by other dusty space junk over the course of billions of years. The frosty rings, however, were too new and polished to be ancient.

This, combined with other data, has led many Saturn experts to believe that the rings first emerged some hundreds of millions of years ago. If they didn’t originate during the chaos of the early solar system, when massive objects were constantly crashing into one another, then they likely emerged during the peaceful times of the recent astronomical past. However, how?

At now, Saturn possesses at least 145 moons, and it likely had much more before its rings formed. A two-moon collision has been postulated by scientists as the result of the sun’s enormous pull progressively destabilising the orbits of some of the moons.

According to the new research, if two ice satellites were to collide, Saturn would be showered with a lot of frozen confetti. Those rings may emerge if ice made it over the Roche limit, the point at which a planet’s gravitational tides begin to break apart moons.

It’s possible that fragments that remained beyond the boundary collided with other satellites, shattering them and releasing additional material, the kind that may eventually coalesce into new moons.

Which of the existing moons is a juvenile is unclear. However, Saturn’s moon Rhea, which is second in size only to Titan, may serve as an illustration. If it were older, it would have experienced more gravitational fluctuations over time, making its orbit more erratic. Rhea, on the other hand, has a round shape and a flat surface, indicating that it originated only recently, maybe using the newly available material for moons.

Potentially livable subterranean waters exist on some of Saturn’s moons. However, this may be less likely to occur if those moons are younger than previously thought.

Unfortunately, this research won’t put an end to the ongoing controversy about where Saturn’s halos came from. Instead of being permanent ornaments, the rings are shown to be transient and dynamic.