The James Webb Space Telescope finally arrived at its new home on Monday, after a journey of over one million miles. The arrival of the spacecraft marks the completion of another difficult stage as scientists on Earth prepare to spend at least a decade using the observatory to study distant light that has existed since the beginning of the universe.

On December 25, the telescope was launched into orbit, and astronomers all around the globe held their collective breaths. The $10 billion telescope, on the other hand, still needed to go through the first leg of its installation phase. Astronomers were allowed to take a deep breath again earlier this month when the observatory’s heat shield was unfolded and its mirrors and other equipment were deployed without incident – a remarkable accomplishment considering the telescope’s innovative design and technical complexity.

Engineers reported on Monday at 2:05 p.m. Eastern time that the James Webb Space Telescope had successfully arrived at its final destination.

After a last, about five-minute fire of the spacecraft’s primary motor, the telescope was able to sweep itself into a tiny pocket of stability where the gravitational pulls of the sun and the Earth converged, allowing it to see objects beyond the moon. The Webb telescope will be pulled around the sun alongside Earth for years from this outpost, which is known as the second Lagrange Point or L2. This will allow the telescope to keep a constant watch on distant space without using much fuel to maintain its position.

This new space telescope, named for a former NASA administrator who led the early years of the Apollo programme, is seven times more sensitive and three times larger than the Hubble Space Telescope, which has been operating for over 32 years and is three times the size of the Hubble. The Webb Space Telescope, which is a follow-up to the Hubble Space Telescope, is intended to view farther into the past than its famed predecessor in order to study the first stars and galaxies that twinkled alive at the beginning of time, 13.7 billion years ago.

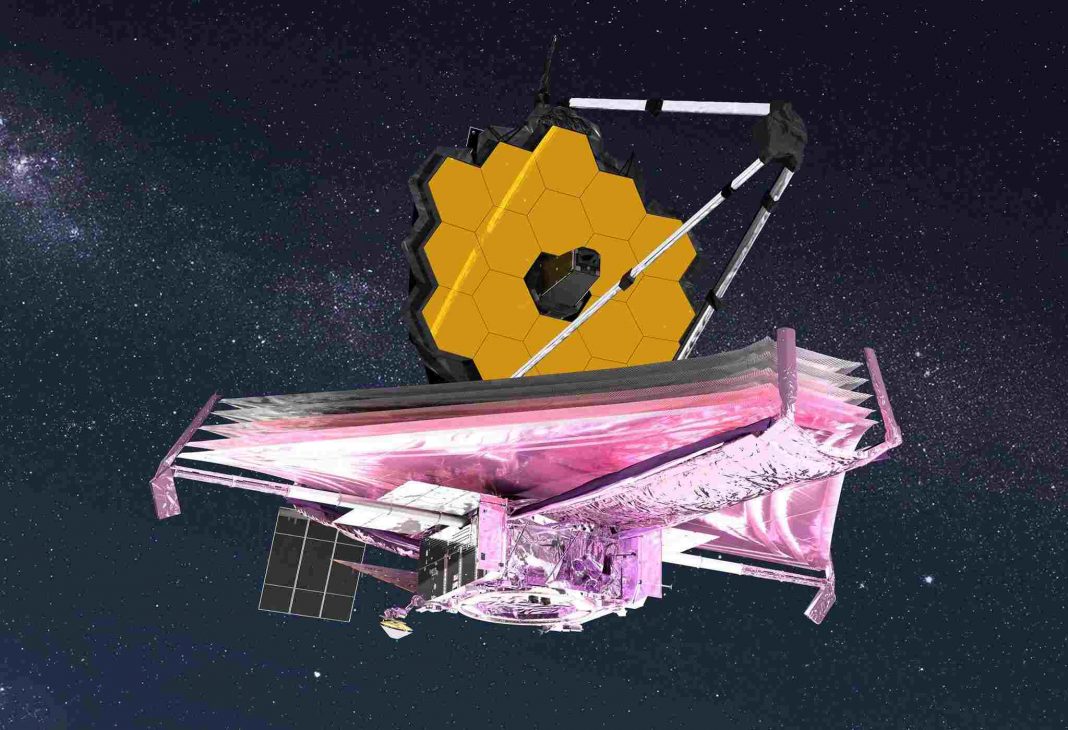

The launch of Webb on Christmas morning brought to a close a dangerous 25-year development timetable characterised by technical hurdles, blunders, and cost overruns that made the spacecraft’s journey to orbit all the more nerve-wracking for astronomers and space agency managers. The telescope, which had been compressed to fit aboard a European Ariane rocket, unfolded hundreds of mechanical limbs and equipment as it was launched into space. To protect Webb’s equipment from the heat of the sun, five layers of a thin foil-like plastic were stretched tight to the size of a tennis court. An hour later, the telescope opened its doors to reveal a 212 foot-wide array of 18 gold-plated mirrors, which will assist it in reflecting light from the universe onto the telescope’s ultrasensitive infrared sensors.

It will be very cold on the instrument side of the telescope, as it is facing away from the sun, yet the other side, or the outermost layer of the sun shield, will have temperatures as high as 230 degrees Fahrenheit deflected off of it. As a result, Webb’s architecture is able to meet a critical challenge: keeping the telescope’s sensors cold so that stray heat does not interfere with its infrared scans of ancient galaxies, distant black holes, and planets circling other stars.

As a bonus, locating the telescope in the L2 neighbourhood helps to maintain cool temperatures while also giving adequate sunshine for the Webb’s solar panels, which produce power. However, the telescope will not be stationed at the exact location of L2; instead, it will rotate about the centre of the point once every 180 days in an orbital ring more than 500,000 miles wide, exposing its solar arrays to sunlight.

After the telescope’s equipment have been deployed and the spacecraft has arrived at L2, it will take months of smaller steps before those of us on Earth will be able to experience the spacecraft’s stunning vistas of the universe for ourselves. The Webb’s 18 hexagonal pieces in its array will function as a single mirror, and engineers will watch as algorithms help fine-tune the position of the Webb’s mirror segments, correcting any misalignments as accurately as one-10,000th of a hair follicle — to allow the 18 hexagonal pieces in its array to function as a single mirror.

Once the Webb’s scientific equipment have been calibrated and tested, engineers will need to check the telescope’s capacity to latch onto known objects and follow moving targets before astronomers can begin using the telescope for science operations this summer. In an online webcast on Monday, Amber Straughn, a deputy project scientist for the telescope, said that the first year of observations with the Webb Space Telescope has already been set.