During the same time as nurses and physicians are dealing with a record-breaking influx of Omicron cases, evolutionary scientists are engaged in their own struggle: finding out how this world-dominating variety came to be.

It was the genetic nature of the Omicron variety that first caught the attention of scientists when it took off in southern Africa back in November. When compared to prior coronavirus variations, which changed from the original Wuhan form by a dozen or two mutations, Omicron had 53 mutations, representing a startlingly huge leap in viral development.

An international team of scientists published a report online last week that added to the mysticism surrounding the phenomenon. They discovered that 13 of the changes were seen very seldom, if at all, in other coronaviruses, indicating that they should have been damaging to the Omicron virus. When taken together, these mutations seem to be needed for several of Omicron’s most critical tasks, rather than being isolated.

At this point, scientists are attempting to determine how Omicron broke the usual norms of evolution and exploited these mutations in order to become such an effective carrier of infectious illness.

A coronavirus’s existence is characterised by the occurrence of mutations on a regular basis. It’s possible that a virus may make a faulty copy of its genes every time it multiplies inside of a cell, although this is a remote possibility. In many cases, new viruses would be dysfunctional and unable to compete with existing viruses as a result of those alterations.

However, a virus may benefit from a mutation as well. It might, for example, cause the virus to adhere more securely to cells or to multiply more quickly than usual. Viruses that have inherited a favourable mutation may be able to outcompete their competitors.

Over the course of the year 2020, scientists discovered that separate lineages of the coronavirus from different parts of the globe progressively acquired a number of mutations. It took until the end of the year for the evolutionary process to become sluggish and steady.

In December 2020, researchers in the United Kingdom were shocked to find a novel coronavirus variant in England that included 23 mutations not identified in the initial coronavirus isolation from Wuhan a year earlier.

That variation, which was eventually dubbed Alpha, quickly rose to prominence around the globe. Other rapidly spreading versions appeared during the course of the year 2021. While some variants were restricted to certain regions or continents, the Delta version, which had 20 unique mutations, defeated the Alpha variant and took over as the dominant variety throughout the summer.

Then there was Omicron, who had nearly twice as many mutations as the previous generation. After discovering Omicron, Dr. Martin and his colleagues set out to recreate the variant’s extreme development by comparing its 53 mutations with those of other coronaviruses. They were successful in their endeavours. The presence of several mutations that were shared by Omicron, Delta, and other variations suggested that they had originated more than once and that natural selection had favoured them on a number of different occasions.

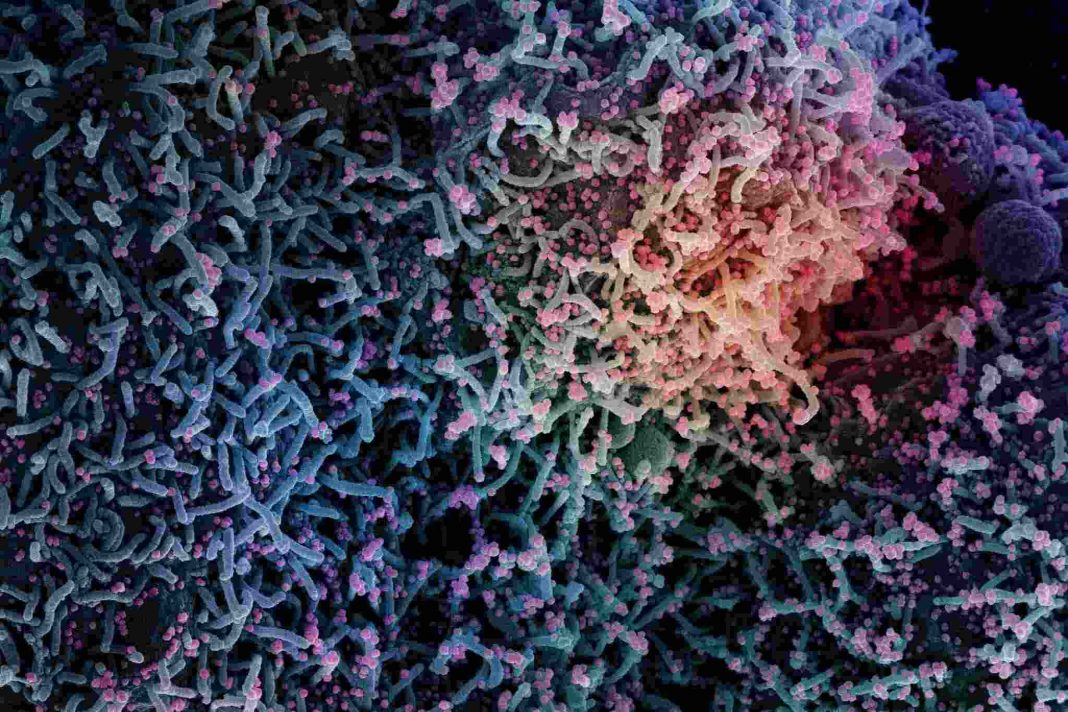

When the scientists looked at the “spike” protein that studs Omicron’s surface and lets it to latch on to cells, they saw a completely different pattern than they had anticipated.

The spike gene in Omicron has 30 different mutations. The researchers discovered that 13 of them were exceedingly uncommon in other coronaviruses, including their distant viral relatives found in bats, which led them to believe that they were unique. In the millions of coronavirus genomes that scientists have sequenced during the course of the pandemic, only a small number of the 13 had previously been identified.

James Lloyd-Smith, a disease ecologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the research, said that the findings demonstrated how difficult it is to recreate the development of a virus, especially one that has just recently emerged.