It appears that a woman of mixed race has become only the third person ever to be cured of HIV, thanks to a new transplant method involving umbilical cord blood that opens up the possibility of curing more people from diverse racial backgrounds than was previously possible, according to scientists who announced their findings on Tuesday.

Compared to adult stem cells, which were utilised in the bone marrow transplants that healed the previous two patients, cord blood is more readily accessible, and it does not need to be as tightly matched to the recipient as adult stem cells do. Scientists believe that since the majority of donors in registries are of Caucasian descent, allowing for merely a partial match has the potential to cure hundreds of Americans who are infected with HIV and have cancer each year.

The lady, who was also suffering from leukaemia, was given cord blood in order to cure her disease. A partly matched donor was used instead of the more traditional method of locating a bone marrow donor who was of a similar race and ethnicity to the patient. During the transplantation process, she also got blood from a close relative to provide her body with temporary immunological responses.

Women are assumed to advance more slowly through H.I.V. infection than males, yet despite the fact that women account for more than half of all H.I.V. infections in the globe, they account for just 11 percent of those who participate in treatment studies.

Antiretroviral medications are effective in controlling H.I.V., but a cure is required to put an end to the decades-old epidemic. Around the world, roughly 38 million people are infected with HIV, with around 73 percent of those infected receiving treatment.

For the vast majority of patients, a bone marrow transplant is not a viable choice. Because such transplants are very intrusive and hazardous, they are often reserved for cancer patients who have exhausted all other treatment options. Nonetheless,

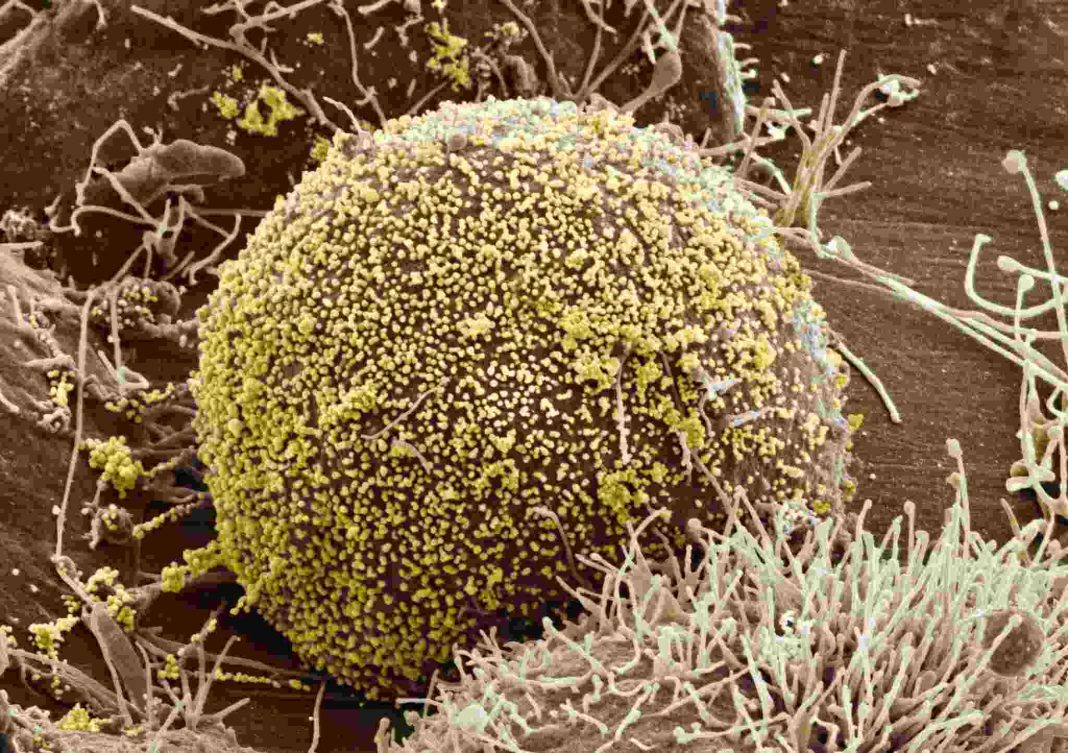

In all cases, the men got bone marrow transplants from donors who contained a mutation that prevents the transmission of the HIV virus. Only roughly 20,000 donors have been discovered as having the mutation, with the majority of them being of Northern European heritage.

Due to the fact that bone marrow transplants replaced all of the immune systems in both of the prior instances, both men had severe adverse effects, including graft versus host disease, a condition in which the donor’s cells attack the recipient’s body. Mr. Brown came dangerously close to death after his transplant. Even though Mr. Castillejo’s therapy was less intensive, his physicians report that he lost approximately 70 pounds in the first year after his transplant, as well as developing a hearing loss and surviving various infections.

According to Dr. JingMei Hsu, the patient’s physician at Weill Cornell Medicine, the lady in the most recent example was discharged from the hospital on day 17 after her transplant and did not develop graft versus host disease as a result of the procedure. Dr. Hsu believes that the mix of cord blood and her relative’s cells may have prevented her from experiencing many of the severe side effects associated with a traditional bone marrow transplant.

“Previously, it was speculated that graft versus host illness could have had a role in the success of earlier HIV cures,” said Dr. Sharon Lewin, president-elect of the International AIDS Society, who was not involved in the research. Dr. Lewin said that the new findings refute such notion.

Hepatitis C virus (HIV) was discovered in June 2013 in the blood of a lady who is now beyond middle age (she did not want to divulge her precise age because of privacy concerns). Her virus levels were maintained under control by antiretroviral medications. She was diagnosed with acute myelogenous leukaemia (AML) in March of this year.

When she was eighteen months old, she got cord blood from an anonymous donor who had the mutation that prevents H-I-V from entering cells. Due to the fact that cord blood cells may take up to six weeks to fully engraft, she was also given partly matched blood stem cells from a first-degree cousin in the meanwhile.

Dr. Marshall Glesby, an infectious diseases expert at Weill Cornell Medicine of New York who was a member of the research team, explained that the half-matched “haplo” cells from her relative helped to maintain her immune system until the cord blood cells took over, making the transplant much less dangerous.

The patient made the decision to stop taking antiretroviral medication 37 months following the donation. Blood tests have shown that she no longer has any detectable antibodies to the virus, despite the fact that she has been infected with the virus for more than 14 months.

Experts say they are baffled as to why stem cells derived from cord blood seem to function so effectively. According to Dr. Koen Van Besien, head of the transplant programme at Weill Cornell Medical College, one theory is that they are better capable of adjusting to a new environment. As he said, “These are infants, therefore they are more adaptive.”

In addition to stem cells, cord blood may include other components that benefit in the transplantation process.