The European Space Agency stated on Monday that the planned launch in 2022 of a European space mission with Russia to put a robot on Mars is now “extremely uncertain.”

The European Union has imposed sanctions on Russia as a consequence of the country’s invasion of Ukraine, and it is probable that the mission will be postponed. Civil space cooperation between Russia and Western nations has been growing for decades, despite the fact that there are still conflicting regions on the ground. However, the armed situation in Ukraine has hampered both sides’ capacity to distinguish between what happens in space and what happens on the planet’s surface, as well as their ability to communicate effectively.

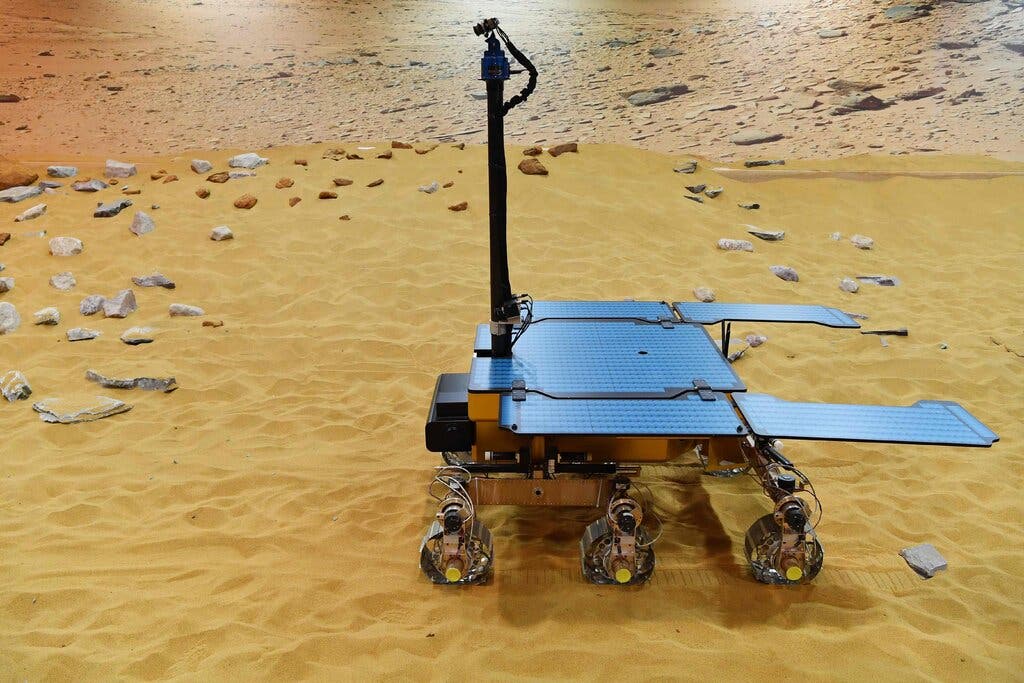

A launch from a Russian-owned spaceport in Kazakhstan was slated to take place in the autumn of this year for the ExoMars project, which comprises a robotic rover manufactured by the European Space Agency and a landing platform provided by Russia. The two partners would next try a landing in 2023 that would contain a rover called Rosalind Franklin, which was named after an English scientist who was instrumental in discovering the structure of DNA.

Nevertheless, the European Space Agency (ESA), a group of 22 European countries, issued a brief statement in which it expressed regret for the “human casualties and tragic consequences of the war in Ukraine.” The statement added that “the sanctions and the wider context make a launch in 2022 very unlikely.”

The ESA announcement almost guarantees that the ExoMars mission would be delayed for at least another two years. The project’s cameras, sensors, and a drill will scour the Martian surface in search of signs of possible ancient life. Journeys to Mars are normally launched within a window of about every two years when the red planet is aligned with the Earth, allowing for a quicker travel to the red planet. Prior to this, funding and technical concerns have caused the mission to be postponed from its planned launch in 2018. The Covid-19 epidemic, as well as technological difficulties, were the causes of the mission’s most recent postponement, which occurred in 2020.

The situation aboard ExoMars is the latest example of the consequences of Russia’s invasion of civil space. According to a statement released last week by Russia’s space agency, Roscosmos, the country’s workhorse Soyuz rocket launches at the European Space Agency’s launchpad in French Guiana will be suspended, and 87 Russian personnel will be evacuated from the site, effectively “suspending cooperation with European partners in the organisation of space launches.” In the following months, this might have an impact on at least four European missions.

It has also thrown into doubt the future of other international space collaborations, such as those onboard the International Space Station, a space scientific laboratory in orbit that is principally operated by NASA and the Russian space agency, Roscosmos. The relationships that have formed the foundation of the two-decade-old station, which has served as a symbol of post-Cold War diplomacy, have survived several geopolitical battles on Earth.

The space station is powered by both energy from the American part and the engines of Russian spacecraft that are docked to it in order to maintain its orbit. When the space shuttles were decommissioned in 2011, NASA began relying on Russian rockets to deliver its astronauts into orbit, a practise that began in 2011. Then, in 2020, SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft started transporting NASA astronauts to the International Space Station. Earlier this year, the two parties were in talks on flying Russian astronauts on the SpaceX rocket.

Despite the fact that the United States and Russia recently enacted stricter export control legislation for commerce in technology, NASA said that the new rules would “continue to facilitate U.S.-Russia civil space cooperation.” Also on Monday, Kathy Lueders, NASA’s head of space operations, said that she saw no evidence that Russia’s commitment to the International Space Station was weakening, and that the agency did not need to make plans to keep the space station in orbit if it did not get Russian assistance.