As Richard Stockton Rush III loved to remark, the goal from the beginning was to break new ground. One of them had a lot of expertise with new businesses and was very into the idea of “making humanity a multiplanet species.” Mr. Rush, the other, was an aeronautical engineer and wealthy investor. Each once harboured aspirations of exploring deep space.

According to Mr. Sohnlein, OceanGate’s founders wanted to follow the lead of entrepreneurs like Elon Musk in democratising space flight by making deep-sea exploration available to rich visitors and scholars.

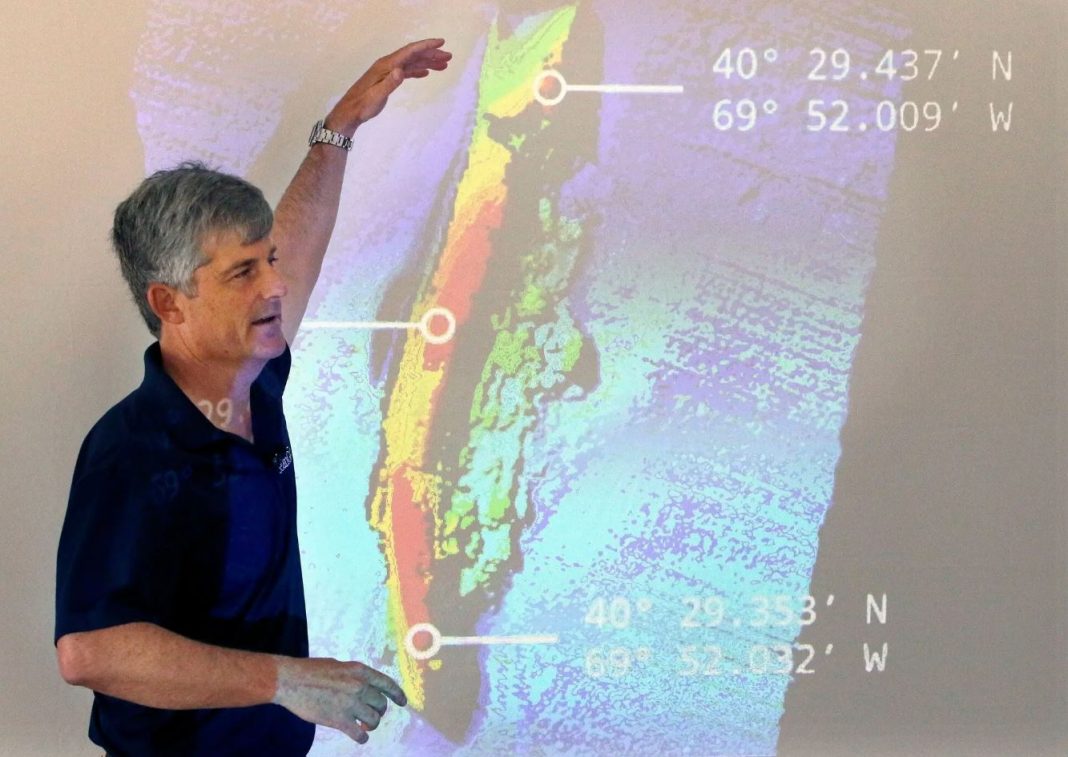

Authorities have begun mapping the wreckage of the Titan submarine on the ocean bottom near the Titanic catastrophe, and their attention has shifted to the business at the heart of the project. Titan’s unique design was a calamity waiting to happen and required thorough testing, so the tragedy that rocked the globe and enthralled the country this week did not come as a surprise to seasoned deep-sea explorers.

Mr. Rush’s self-assurance may have been hardwired into him. He was descended from two signers of the Declaration of Independence and was the heir of an oil wealth in San Francisco. His maternal grandmother, Louise Davies, was a major arts supporter on the West Coast, thus she was honoured with the naming of the San Francisco Symphony Hall in her honour.

His family was friendly with the Conrads, including Pete, the Apollo 12 commander Charles Conrad Jr. Mr. Rush once stated that he had asked Mr. Conrad how he might become an astronaut like him, and that Mr. Conrad had told him to join the military and get his pilot’s licence. According to his corporate description, he got a degree in aeronautical engineering from Princeton in 1984 while working summers as a pilot in Saudi Arabia.

Mr. Rush claimed that he wanted to be a fighter pilot but couldn’t because of his poor vision, so he settled for a job as a flight test engineer at McDonnell Douglas in the Pacific Northwest instead. He wed pilot Wendy Weil in 1986; she was a descendant of Isidor Straus, a co-owner of Macy’s who, together with his wife Ida, perished in the sinking of the Titanic in 1912.

He considered taking a private rocket to orbit in the early 2000s after investing a portion of his fortune on a number of other technological and technical endeavours.

After witnessing the successful 2004 launch of SpaceShipOne in the Mojave Desert, the first privately financed human vehicle flown into space, his enthusiasm in being a simple passenger suddenly waned, and he told Smithsonian magazine, “I didn’t want to go up into space as a tourist.” I always saw myself as a potential Enterprise captain.

Mr. Rush has been a qualified scuba diver since he was 14 years old, and he credits a dip in Puget Sound, where the water was so frigid that it inspired him to consider getting a miniature submarine so he could explore the ocean in more comfort. He claimed to have developed a 12-foot mini-sub with a plexiglass window in 2006 after realising there were very few submarines available on the private market. The schematics for the sub had been drawn up by a former U.S. Navy submarine captain.

I grew quite invested in the project. Two years later, Graham Hawkes, an engineer and longstanding submersible specialist, introduced Mr. Sohnlein and Mr. Rush. Mr. Hawkes recognised Mr. Rush as an entrepreneur on Thursday, one who sought to carve out a special place for himself in the growing extreme tourism industry. Mr. Rush showed interest in purchasing Mr. Hawkes’ submersibles business for a while, but a sale never materialised.

Before upgrading to the deeper-diving steel-hulled cylinder Cyclops 1, the firm employed a used yellow submersible for shallow dives. However, maintaining and moving the steel-hulled vessel proved a prohibitive financial burden.

In 2013, Mr. Sohnlein left OceanGate, believing that the company had graduated from its infancy and into Mr. Rush’s area of expertise in engineering. According to Mr. Sohnlein, Mr. Rush started publicly discussing plans to construct a titanium-capped prototype of Cyclops 1 out of lightweight carbon fibre shortly after he departed.

This week, Mr. Hawkes expressed regret for not disclosing to Mr. Rush that carbon fibre was too unreliable to use in the shell of a submersible, which must resist tremendous pressure. He added that one day it may descend to 10,000 feet without incident, but the following day it could sustain undetectable damage and collapse at 9,000 feet.

Submersible Titan, which could carry five people and dive eight times as deep as Cyclops, was advertised by OceanGate for trips to the Titanic wreck in 2017. OceanGate initially announced that each visitor would be charged about $105,000, which was the adjusted cost of a first-class ticket on the Titanic in 1912.

Concerns were raised among those involved in deep-sea research. Director of maritime operations at OceanGate David Lochridge had begun writing a report in January 2018 warning of the risks to passengers.

Karl Stanley, who has run a tourist submersible in Honduras for decades, claims that at a symposium of crewed underwater vehicle specialists in New Orleans a few weeks later, he and a few other experts got into an argument with Mr. Rush. Mr. Stanley said that the room’s occupants had “ganged up” on the man.

After a shaky start, OceanGate was successfully leading Titanic missions in 2021 at a cost of $250,000. According to court records submitted by the corporation, 28 passengers boarded Titan in 2022.