An anonymous Facebook user account was established on Feb. 4, 2019, by a Facebook researcher in order to explore what it was like to use the social media platform as someone who lived in Kerala, India.

For the following three weeks, the account functioned under a single rule: adhere to all of the suggestions given by Facebook’s algorithms, which included joining groups, watching videos, and exploring new sites on the social networking site.

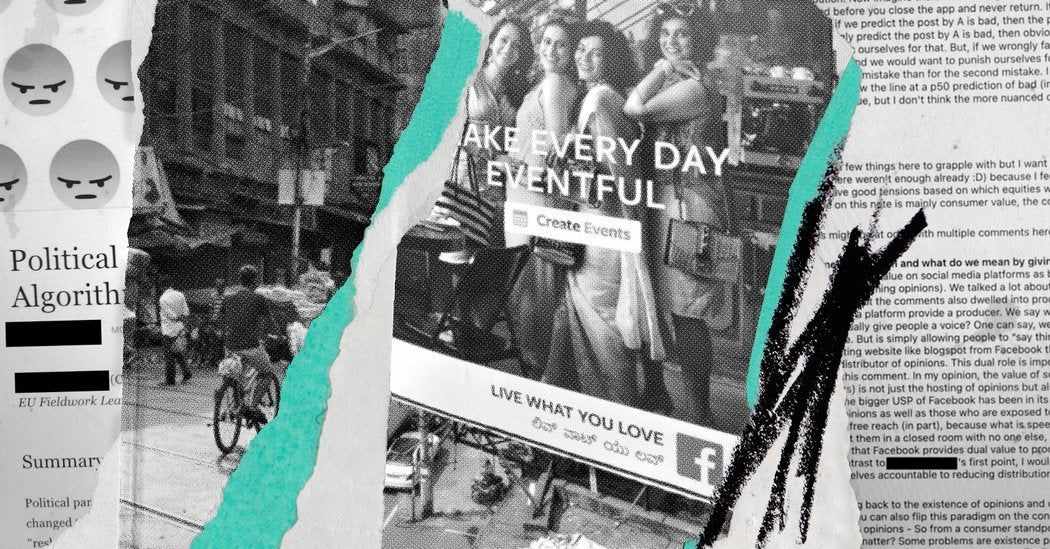

There was a flood of hate speech, disinformation, and celebrations of violence as a consequence, which was recorded in an internal Facebook report that was released later that month and was widely shared.

The paper was one of hundreds of studies and memoranda made by Facebook workers who were concerned about the impact of the social media network on the country. They give compelling proof of one of the most significant complaints levelled against the multinational corporation by human rights activists and lawmakers throughout the world: It enters a nation without fully comprehending the possible influence on local culture and politics, and it fails to mobilize the necessary resources to address difficulties as they arise after they have occurred.

India is the firm’s biggest market, with 340 million individuals utilizing the company’s different social media platforms, according to the corporation. And Facebook’s challenges on the subcontinent are an exaggerated version of the ones the company has experienced across the globe, which are exacerbated by a lack of resources and a lack of competence in the country’s 22 officially recognized languages.

The internal Facebook papers, which were acquired by a coalition of news organizations, including The New York Times, are part of a larger trove of data known as The Facebook Papers. The New York Times was among the news organizations that got the records. It was Frances Haugen, a former Facebook product manager who turned whistleblower and recently testified before a Senate panel regarding the corporation and its social media platforms, who amassed the collection of data and documents. When Ms. Haugen filed her complaint with the Securities and Exchange Commission earlier this month, she included references to India in many of the papers she submitted.

It is detailed in the papers how bogus accounts related to the country’s governing party and opposition leaders were causing chaos during the country’s recent national elections. A concept championed by Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s top executive, to concentrate on “meaningful social connections,” or exchanges between friends and family, was shown to be contributing to greater disinformation in India, especially during the epidemic.

According to Facebook’s internal records, the company lacked sufficient personnel in India and was unable to deal with the issues it had caused, which included anti-Muslim messages, when it arrived. According to one document describing Facebook’s resource allocation, 87 percent of the company’s global budget for time spent on classifying misinformation is allocated to the United States, with only 13 percent allocated to the rest of the world. This is despite the fact that North American users account for only 10 percent of the social network’s daily active users.

According to Andy Stone, a spokesperson for Facebook, the data are incomplete since they do not include the company’s third-party fact-checking partners, the majority of whom are located outside of the United States.

This disproportionate emphasis on the United States has had negative implications in a number of nations other than India. According to company papers, Facebook used efforts to suppress misinformation during the November election in Myanmar, including disinformation spread by the country’s military junta, in order to protect voters.

Mr. Stone said that Facebook has made considerable investments in technology to detect hate speech in a variety of languages, including Hindi and Bengali, which are two of the most commonly spoken languages in the world. He went on to say that Facebook has cut the amount of hate speech that people see throughout the world in half this year.