At the end of July, Norman Otey required immediate medical attention and was taken by ambulance to Richmond Community Hospital. The elderly man, 63 years old, was hunched down in apparent agony and muttering incoherently. The results of the blood tests pointed to the possibility of septic shock, a serious condition that needed the capabilities and knowledge of an intensive care unit.

According to information provided by his sister, Linda Jones-Smith, the transfer of Mr. Otey to a different hospital took a number of hours to complete. His condition worsened on the way there, and he eventually passed away from sepsis. According to two persons who provided care for Mr. Otey, the delay was most certainly a contributing factor in his death.

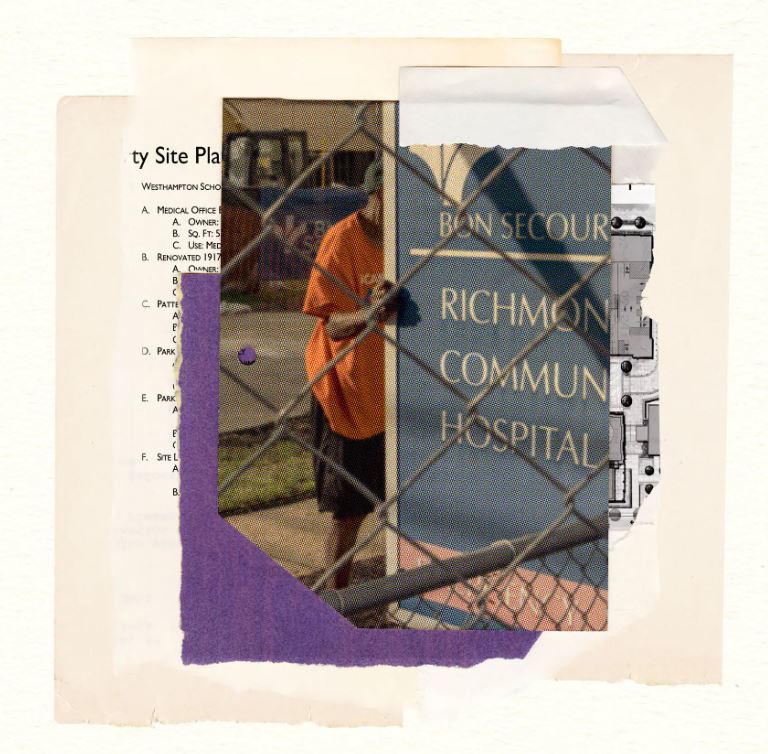

Only a crowded emergency department and a mental facility make up the majority of the Richmond Community, which is surrounded on all sides by public housing developments. It does not have any experts who focus on the kidneys or lungs, nor does it have a maternity ward. According to two medical staff at the hospital, who asked to remain anonymous since they are still employed there, the facility’s magnetic resonance imaging equipment has regular breakdowns and was out of operation for seven weeks over the summer. It is sometimes difficult to get standard instruments such as an otoscope, which is a device used to examine the ear canal.

According to the hospital’s financial data, the hollowed-out hospital, which is owned by Bon Secours Mercy Health, one of the largest nonprofit health care chains in the country, has the highest profit margins of any hospital in Virginia, generating as much as $100 million each year. This is despite the fact that the hospital is almost entirely devoid of patients.

A government programme that enables clinics in low-income areas to purchase prescription pharmaceuticals at substantial discounts, charge insurers the full amount, and keep the difference in their own pockets has been the driving force behind the organization’s remarkable level of success. According to two former executives who were aware with Richmond Community’s finances and who asked to remain anonymous because they now work in the health care business, the programme is responsible for the overwhelming bulk of the hospital’s revenues. This information was provided by the hospital.

The medication programme was developed with the expectation that hospitals would reinvest the windfalls into their facilities in order to enhance the quality of treatment that is provided to low-income patients. According to more than 20 former executives, doctors, and nurses, Bon Secours, which was established by Roman Catholic nuns more than a century ago, has been cutting services at Richmond Community while investing in the city’s wealthier, whiter neighbourhoods. Bon Secours was founded by nuns who practised Roman Catholicism.

Many of these institutions have been cutting their personnel levels for years, leaving them unprepared for the influx of patients who suffer Covid-19-related serious illnesses. Others have coached their personnel to coerce impoverished patients, who ought to be entitled for free medical treatment, into making payments by using strategies that were borrowed from business consultants.

A spokeswoman for Bon Secours Mercy Health said in a statement that the hospital system had spent nearly ten million dollars on improvements to Richmond Community Hospital since 2013. Some of these improvements include the opening of a pharmacy as well as the renovation of the cafeteria, emergency department, and other areas. According to what she said, the chain has also spent close to $9 million in the community that the hospital is located in since 2018.

According to studies carried out by Virginia Commonwealth University in some of the communities that are located in close proximity to the hospital, more than fifty percent of the households do not own a vehicle. It takes more than an hour to make the trip on the public bus to St. Mary’s, which is a huge Bon Secours campus located in the northwest portion of the city. From the East End there is no public transit to go to Memorial Regional, which is located nine miles distant.

This particular service was not provided by Richmond Community. It took more than two weeks to schedule an appointment for Ms. Scarborough at the specialist’s office since she was required to have it done there. After many weeks after the treatment, Ms. Scarborough’s whole toe was removed.

According to a cardiologist and a specialist on racial inequalities in amputation named Dr. Foluso Fakorede, many persons in low-income neighbourhoods that were mostly nonwhite had comparable wait times before undergoing the operation. He said, “I am in no way astonished by the events that have unfolded with this patient at all.”

Since Ms. Scarborough can not drive, her nephew is required to take time off of work in order to accompany her to her appointments with the vascular surgeon. The physician’s office is located around 10 miles from their house. The walk to Richmond Community would have taken no more than five minutes. Regarding her situation, Bon Secours did not provide any response.