A multibillion-dollar illegal drug industry run by powerful associates and relatives of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has risen from the ashes of the country’s ten-year civil war to eclipse the country’s legal exports and transform the country into the world’s newest narcostate, according to the United Nations.

Captagon, an illicit and addictive amphetamine that is popular in Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries, is the company’s main product. Syrian government-run factories make the pills, while packaging plants disguise them for export and smuggling networks transport them to foreign markets are all part of the organization’s activities.

Following an investigation by The New York Times, it was discovered that the Syrian Army’s Fourth Armored Division, an elite unit commanded by Maher al-Assad, the president’s younger brother and one of the country’s most powerful men, is in charge of much of the country’s food production and distribution.

According to The Times investigation, major players also include businessmen with close ties to the government, the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah, and other members of the president’s extended family, whose last name provides protection for illegal activities. The investigation is based on information from law enforcement officials in 10 countries and dozens of interviews with international and regional drug experts, Syrians with knowledge of the drug trade, and current and former government officials.

It developed amid the ashes of a decade-long conflict that had wrecked Syria’s economy and forced the majority of its people into poverty, leaving members of Syria’s military, political, and corporate elite seeking for new methods to make hard money and get over American economic sanctions.

According to a database of worldwide captagon arrests produced by The Times of London, illegal speed has surpassed legitimate items as the country’s most profitable export, by a significant margin.

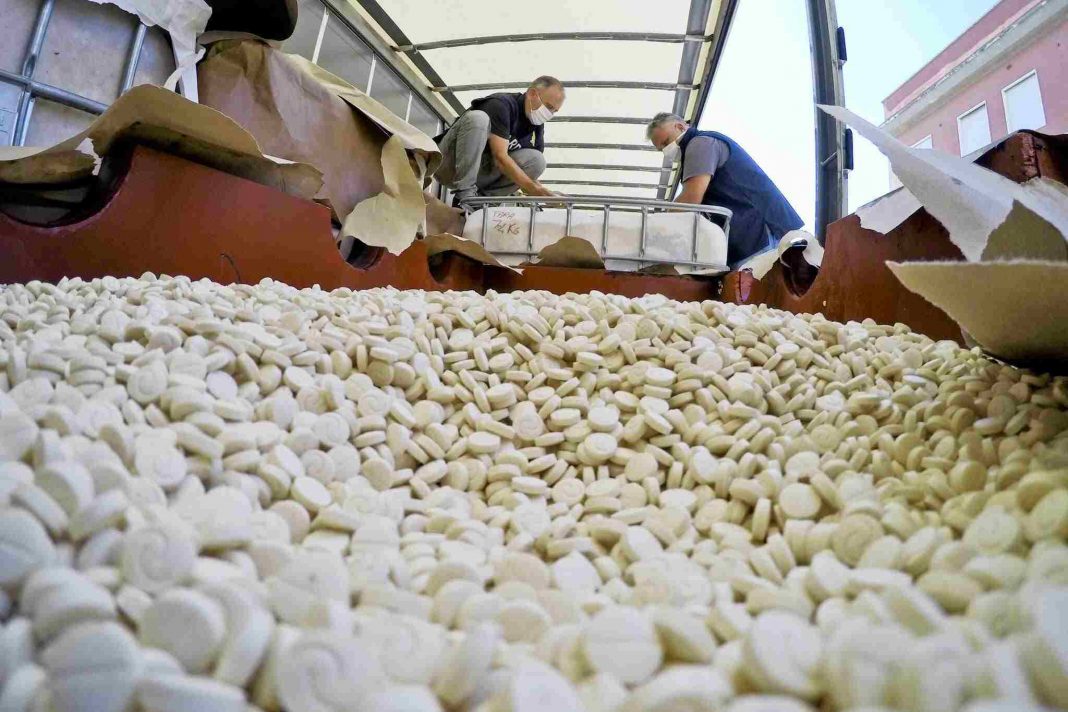

Law enforcement officials estimate that the street value of some of the hauls could exceed $1 billion. In recent years, the authorities in Greece, Italy, Saudi Arabia, and other countries have seized hundreds of millions of pills, the majority of which were sourced from a single government-controlled port in Syria, according to law enforcement officials.

Last year, authorities in Italy discovered 84 million pills concealed among large rolls of paper and metal gears. In March, Malaysian authorities found more than 94 million tablets that had been packed within rubber trolley wheels.

According to drug specialists, these seizures are likely to represent a small proportion of the total amount of pharmaceuticals delivered. In addition to providing insight into the extent of the sector, they also show that its growth in recent years has been rapid and unprecedented.

Since the beginning of this year, more than 250 million captagon tablets have been confiscated throughout the world, an increase of more than 18 times the number seized only four years ago.

Even more worrying for countries in the area is the fact that the Syrian network established to transport captagon has expanded to include the smuggling of more deadly substances, such as crystal meth, according to regional security authorities.

Officials claim that the most significant hurdle to combatting the trade is because it enjoys the support of a government that has no incentive to assist in its abolition.

Following the outbreak of the Syrian war, traffickers took advantage of the confusion to sell the substance to warriors on both sides of the conflict, who used it to boost their confidence while fighting. It was created by enterprising Syrians, who collaborated with local pharmacists and utilised equipment from decommissioned pharmaceutical plants to create it.

Syria has all of the necessary components, including expertise in drug mixing, companies that produced items to hide pills, access to Mediterranean shipping lanes, and well-established smuggling routes to Jordan, Lebanon, and Iraq, among others.

After several years of fighting, the country’s economy collapsed, and an increasing number of Mr. al-cronies Assad’s were targeted by international sanctions as the conflict continued. Captagon was one among the investments made by some of them, and a state-linked cartel formed, bringing together military personnel, militia leaders, businessmen whose companies had prospered throughout the conflict, and relatives of President Bashar al-Assad.

In regions where narcotics are made — in Hezbollah-controlled territory near the Lebanese border, outside Damascus, and in the vicinity of the coastal city of Latakia – Captagon laboratories are distributed throughout government-held sections of Syria, according to Syrians.

According to two Syrians who have seen the factories, many of them are modest, housed in metal hangars or vacant houses, where employees blend chemicals with mixers before pressing them into pills using rudimentary machinery. Soldiers are stationed at a number of sites. Others are marked with signs indicating that they are closed military zones.

Originally a modest livestock trader, Mr. Khiti transitioned into a smuggler during the war, smuggling food and other supplies between Damascus and the rebel-held suburbs with the support of the Syrian government, according to Sami Adel, an activist from Mr. Khiti’s hometown who has followed his career to its conclusion.

Captagon is still manufactured in Lebanon and smuggled out of the country via the country’s borders. According to regional security authorities and Syrians with knowledge of the drug trade, Nouh Zaiter, a Lebanese drug king who now spends most of his time in Syria, serves as a conduit between the Lebanese and Syrian sides of the drug trade.