For some months, researchers from all around the globe have been looking at instances of severe hepatitis, often known as inflammation of the liver, that appeared in youngsters who were otherwise healthy. According to the World Health Organization, there have been at least 920 probable cases found in 33 different countries since October. There have been 18 recorded fatalities and around 5 percent of patients have needed liver transplants.

There has not been a clear explanation provided as of yet. A considerable percentage of hepatitis cases in youngsters have traditionally remained unexplained. There is currently a lack of agreement over whether or not such instances are becoming more prevalent, and it is unclear if the newly documented cases, which are still uncommon, are part of a new medical phenomena or share a root cause.

Two new studies that were published in the New England Journal of Medicine on Wednesday report that in recent months, the number of children presenting at two different medical centres with acute cases of hepatitis that cannot be explained has increased. One of these medical centres is located in Birmingham, Alabama, and the other is located in Birmingham, England.

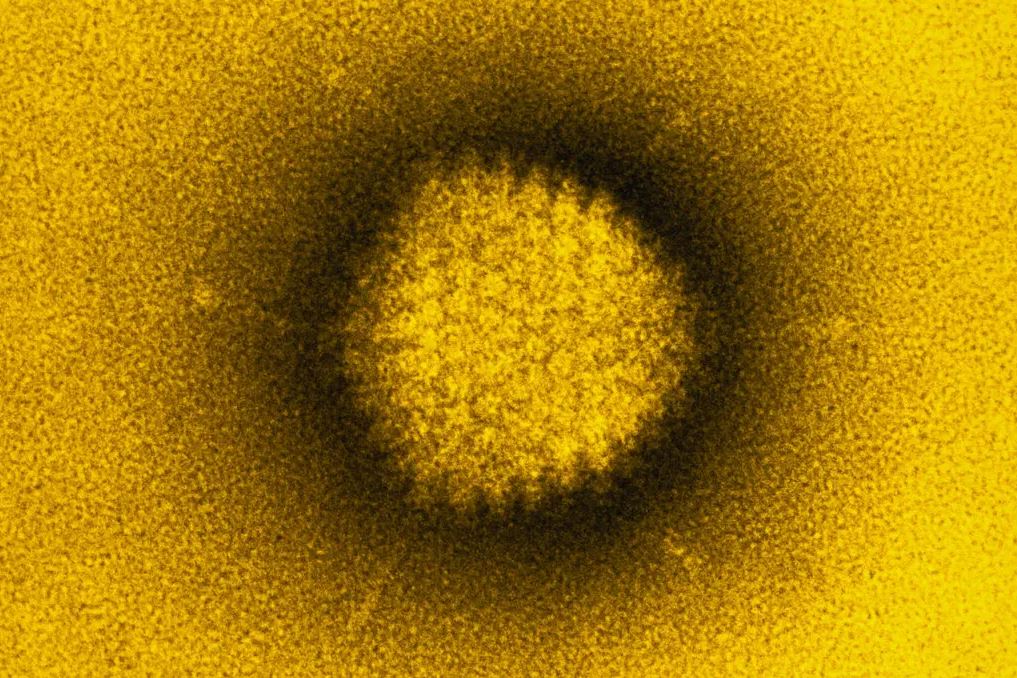

In addition, the study provides more circumstantial evidence that adenovirus 41, a virus that often causes symptoms related to the digestive system, may be a significant role. In both investigations, adenovirus infections were discovered in nearly 90 percent of children examined, and children who experienced acute liver failure or needed transplants had greater average levels of the virus in their blood than those with milder symptoms.

However, the evidence is not even close to being conclusive. In addition, none of the studies revealed conclusive evidence that the virus was present in the liver cells of any of the children who were afflicted, which showed that if there was a connection between adenovirus infections and hepatitis, it may not be a simple one.

He pointed out that not all medical facilities had witnessed the same increase in cases, and a recent study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention did not find any evidence to suggest that unexplained hepatitis had become more prevalent among children in the United States as a whole.

In otherwise healthy youngsters, adenoviruses, which are members of a family of viruses that often produce symptoms similar to the common cold or the flu, are not frequently related with liver inflammation.

But physicians have discovered adenovirus infections in several of the new cases, notably in a group of youngsters in Alabama, the first cluster of cases recorded in the United States.

In one of the recent studies, further information is presented about the hepatitis patients that were treated at the Children’s of Alabama hospital in Birmingham. The number of children hospitalised to the hospital suffering from acute hepatitis for which the cause could not be determined increased to nine over the period of time spanning October 2021 through February 2022, which is three times as many as were admitted during the whole of the year before.

Eight of the nine children’s blood tests came back positive for the presence of an adenovirus. The genetic sequences obtained from viral samples taken from five youngsters were of sufficient quality to warrant additional investigation; they were all found to be adenovirus 41.

In Britain, 44 children with acute, unexplained hepatitis were sent to the paediatric liver transplantation department at Birmingham Women’s and Children’s between Jan. 1 and April 11 in 2022. Thirteen were hospitalised, higher than the one to five people admitted in the same time range in prior years.

The adenovirus was detected in 27 out of the 30 youngsters that were tested for it. The U.K. Health Security Agency eventually discovered that the virus was adenovirus 41, said Dr. Chayarani Kelgeri, consultant paediatric hepatologist at Birmingham Women’s and Children’s and an author of the paper.

When the investigators evaluated liver samples from a subgroup of afflicted youngsters, the picture got more convoluted. The liver cells themselves did not contain any detectable levels of viral proteins or particles, according to the laboratory testing.

It’s possible, she added, that an infection with an adenovirus causes an aberrant immune reaction in certain children, and it’s this immunological response—not the virus—that causes damage to the liver, rather than the virus itself.

However, the reason why certain hospitals are reporting an increase in instances is still a mystery. If hepatitis has only ever been a very uncommon consequence of adenovirus infections in children, we could see an increase in the number of cases if the virus becomes more widespread. According to Dr. Kelgeri, the newly reported instances of hepatitis in Britain have occurred at the same time as “a report of increasing adenovirus” in the general population.

Dr. Karpen said that he did not believe that there was a connection between adenovirus infection and paediatric hepatitis — or that the general prevalence of either condition was growing. He also did not believe that there was a connection between the two conditions. He said that notwithstanding, there is a need for further systematic data gathering and analysis.