These last few months, senior news executives from throughout the United States have convened in an unofficial Zoom conference sponsored by Harvard professors with the objective of “assisting newspaper leaders in their efforts to combat disinformation and media manipulation.”

The seminar at Harvard University’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy gathered an amazing list of executives from major news organisations, including CNN, NBC News, The Associated Press, Axios, and other significant publications in the United States.

Some of them, on the other hand, expressed surprise at the reading packet that had been provided for the first session.

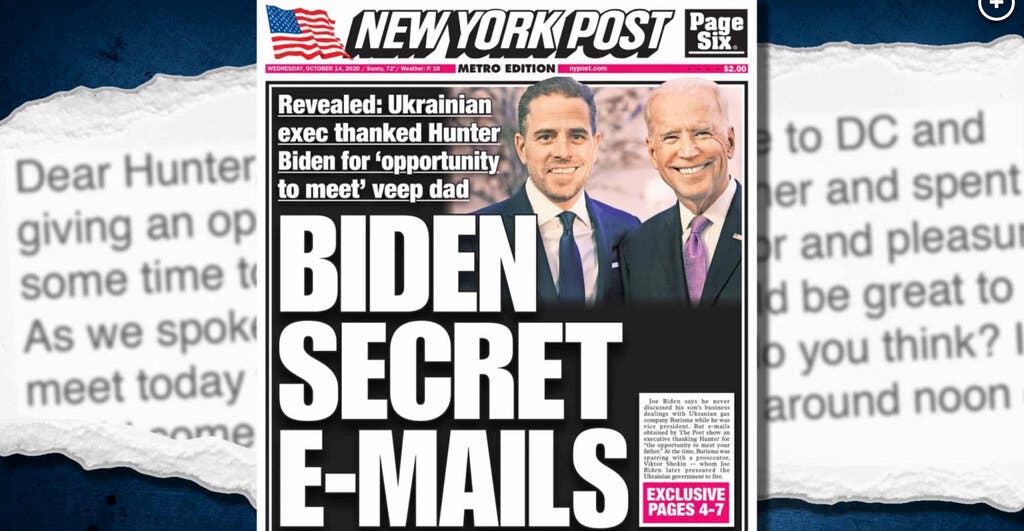

An example from Harvard, which a participant shared with me, was the coverage of Hunter Biden’s misplaced laptop in the last days of the 2020 presidential campaign, which was examined in detail in the case study. According to media reports, the narrative was pushed by advisers and associates of then-President Donald J. Trump, who attempted to convince journalists that the hard drive’s contents would prove the father’s involvement in wrongdoing.

According to the Shorenstein Center’s summation, the news media’s handling of that storey serves as “an illuminating case study on the potential of social media and news organisations to counteract media manipulation operations.”

According to my reporting at the time, the Wall Street Journal took a close look at the topic. Because the Journal was unable to establish that Joe Biden attempted to modify U.S. policy in order to benefit a family member while serving as president, it declined to convey the storey in the manner that Trump advisors desired, instead leaving that spin to right-wing tabloids. What was left was a muddled scenario that is difficult to categorise as “misinformation,” even though some journalists and academics like the clarity of the term “misinformation.” The Journal’s part was, in reality, a fairly conventional journalistic exercise, consisting of a mix of fact-finding and the type of news judgement that has gone out of favour as journalists have become more preoccupied with following social media trends.

“Misinformation,” according to some scholars, is a phrase that should be used with caution; yet, in the instance of the missing laptop, the term was more or less identical with “stuff handed forward by Trump advisers.” And in that sense, the term “media manipulation” refers to any effort by persons whose political views you disagree with to affect news coverage in their favour. According to Emily Dreyfuss, a fellow at the Shorenstein Center’s Technology and Social Change Project, “media manipulation,” despite its negative connotation, is “not always evil.”)

“It is not intended to leave you resolved as a reader,” said Joan Donovan, the research director at Shorenstein who is in charge of the initiative, which has received financing from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. “The Hunter Biden case study is meant to create dialogue,” she said.

Ms. Donovan, a prominent figure on Twitter and a long-time student of the darkest areas of the internet, defined “misinformation” as “false information that is being disseminated.” She was adamant in her opposition to my proposal that the phrase lacked a definite definition.

Ms. Donovan is one of the academics who has attempted to untangle the tangled web of information that characterises current political life. She’s presently addicted to Steve Bannon’s powerful podcast, “War Room,” which she listens to on repeat. She, like many other journalists and academics who study our chaotic media environment, has focused her attention on how trolls and pranksters developed tactics for angering and tricking people online during the first half of the last decade, and how those people applied those tactics to right-wing reactionary politics during the second half of the decade.

In addition to the topic of digital platforms assisting in the propagation of misinformation, the task of spotting stealthy social media operations from Washington to, as my colleague Davey Alba just highlighted, Nairobi, remains very vital. But more importantly, the Covid-19 pandemic has instilled a new sense of urgency in everyone from Mark Zuckerberg to my colleagues at The New York Times about issues such as effectively communicating the seriousness of the pandemic and the safety of vaccines in a media landscape that is rife with false reports.

Politics, on the other hand, is not a scientific discipline. We don’t need to add new jargon to an old-fashioned procedure like news judgement in order to make it more difficult to understand. When we accept jargon-filled new frameworks that we haven’t really thought through, we run the risk of making a mistake. The goal of a reporter is not, in the end, to neatly categorise and identify the news. Its purpose is to communicate what is truly taking place, no matter how untidy and unsatisfactory that may be.