Fermat’s last theorem, a puzzle posed by one of history’s greatest mathematicians, had confounded specialists for more than 300 years until it was finally solved. According to the traditional storey, a genius worked in secret for seven years to find a solution to the problem. Andrew Wiles, a bashful Englishman who achieved fame in the early 1990s, received a dazzling variety of congratulations after announcing his achievement. In 2016, he was awarded the Abel Prize, which is the highest honour in mathematics. It arrived carrying a handbag worth $700,000 dollars.

The storey of Dr. Wiles is being told by a rich Texas benefactor who describes how his financial assistance helped to develop a network of Fermat inventors who, over decades, provided moral and mathematical support to him. It was because of this sponsorship that elite mathematicians were drawn to the challenge after great brains had given up, and it was this patronage that succeeded in reviving the dormant field, which may have made Dr. Wiles’ discovery feasible.

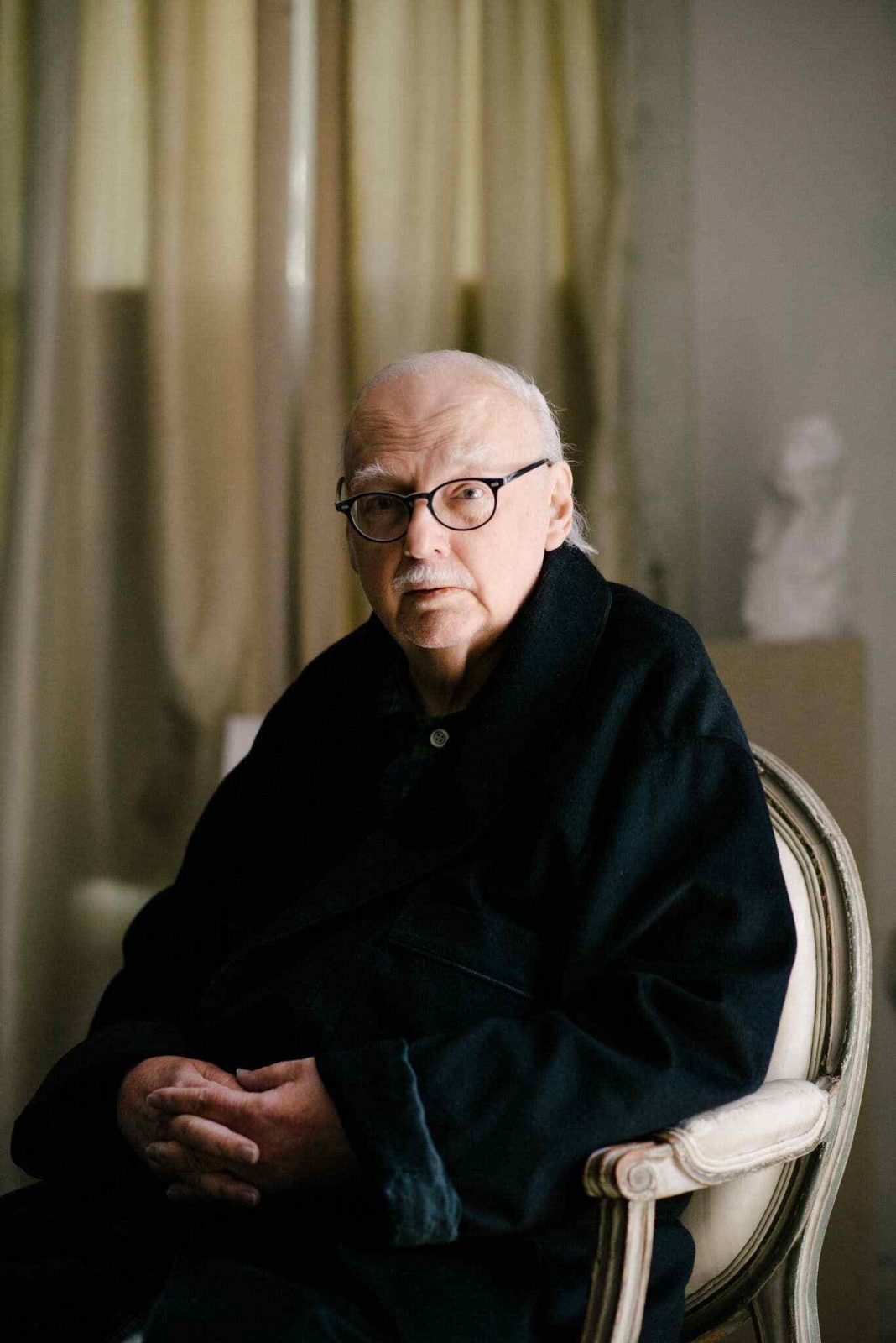

“We were able to resolve the issue,” said James M. Vaughn Jr., 82, president of the Vaughn Foundation Fund, in an interview. “We were able to resolve the issue.” We would still be working on it if we hadn’t put the software together in the way that we did.”

Top experts recognised Mr. Vaughn’s foundation and its early financial assistance as “sparks that ignited an intellectual fire,” albeit they did not go so far as to claim that Mr. Vaughn’s sponsorship was directly responsible for Dr. Wiles’s Fermat discovery. Dr. Wiles did not reply to requests for comment.

The donation of 125 rare and important volumes in the history of mathematics to the University of Texas has inspired Mr. Vaughn to speak openly about other foundation initiatives that have gone virtually unnoticed in the past.

While sociable, Mr. Vaughn, heir to a Texas oil wealth, is a very private individual who has never publicly said that his generosity was the catalyst for the mathematical achievement in question. In spite of this, he is quite pleased with what he considers to be his legacy. Mr. Vaughn said that he and his wife did not have children, and that the Fermat victory was the way he wanted to be remembered in the future.

In the words of Dorian Goldfeld, a professor of mathematics at Columbia University who collaborated closely with Mr. Vaughn, “having someone like Vaughn accomplish this was really crucial.” “It made the issue more evident to a larger number of individuals.” Mr. Vaughn’s financial assistance, he said, ultimately resulted in widespread Fermat partnerships, including an early meeting that Dr. Wiles assisted in putting up.

“It’s fantastic to have individuals like Vaughn,” said Neal I. Koblitz, a professor of mathematics at the University of Washington who worked on a Fermat book for the Vaughn Foundation. “It’s fantastic to have people like Vaughn,” he said. “There was no one working on the issue. Vaughn had the funds as well as the interest.”

It is improbable that Mr. Vaughn had a direct influence on what turned out to be the Byzantine math of the Fermat proof, which was later shown to be the case. In science, however, private benefactors often serve as trailblazers for government financing in tough research projects. That was the case with Mr. Vaughn. He took the initiative, and Washington followed. His millions of dollars in funding for Fermat conferences, writers, and scholars in the 1970s and 1980s revitalised the discipline and increased its social acceptability in the process.

Following that, in the early 1990s, the National Science Foundation, which is a government organisation, provided financial assistance. Dr. Wiles, who was then a professor at Princeton University, received math research grants totalling almost half a million dollars from the foundation.

It turns out that both individuals were attempting to further the study of elliptic curves, a specialised part of mathematics that was previously unknown. As a result of the field’s equations, sets of basic geometric shapes may be constructed, which can lead to endless runs of subsidiary equations and, when solved, solutions to problems of blinding complexity. Dr. Wiles’ discovery of the Fermat breakthrough was prompted by the strange shapes.

Following his appointment as a knight commander of the British Empire, Dr. Andrew Wiles, now 68 years old and known as Sir Andrew, did not respond to several letters seeking his opinion on Mr. Vaughn’s assertion that he was the one who made his achievement possible. A biography of Dr. Wiles describes him as a “diffident” guy who despises publicity and prefers to be in the background.

While historians of science may dispute whether Mr. Vaughn should be given some credit for the Wiles discovery in the future, the growing amount of data already makes the Texan’s frank remark appear less like a yarn and more like a plausible possibility right now.

In an interview with CBS News’ Chris Bryan, a representative for the agency claimed the agency had ultimately tracked down Mr. Vaughn and had assisted in arranging for the transfer of the library to his alma university. When it came to the books, Mr. Bryan expressed concern that they may have been lost to history.

In recent years, Mr. Vaughn has re-emerged as a patron of mathematics, which seems to have reignited his earlier enthusiasm in science. Prior to pursuing a career in mathematics, he wanted to be an astronomer, and he said that he was now pondering whether to put part of his philanthropic efforts toward that discipline.

Despite this, he exhibited no misgivings about his mathematical background and was convinced that history would remember him as having played a pivotal part in the Fermat discovery.